|

The episode happened to the famous alpine

guide Cesare Maestri and to his friend Luciano Eccher, in the summer

1954, on the Campanil Basso, in the Brenta Group.

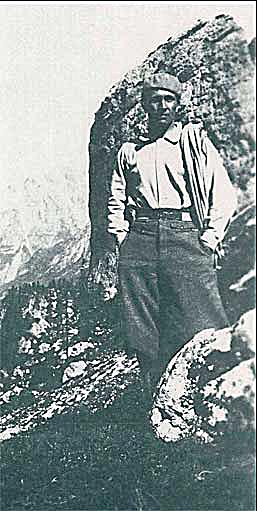

Dino Buzzati, settembre 1929

Dino Buzzati,

Cadin della Neve, settembre1929

The love for the mountains and

in

particular for the Dolomites is in Dino

Buzzati already from an early age:

Mountains! You beautiful, so pure in the purlish dawns /

thrilling in the reddened sunsets /

I would like to be among the giants the giants made of rock who

enter the sky / [...]

You are beautiful, mountains, you are the purest thing, the most

sublime /

I'd like to stay with you in the golden sunsets, when everything

turns red /

I'd like to stay in the azure and misty dawns.

from: “The

mountains' song”, 1920

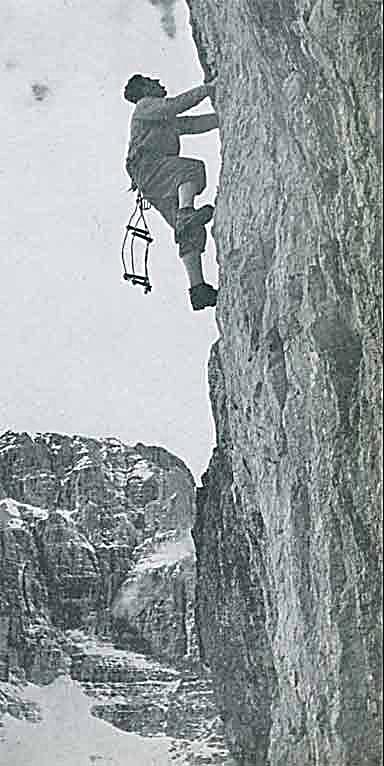

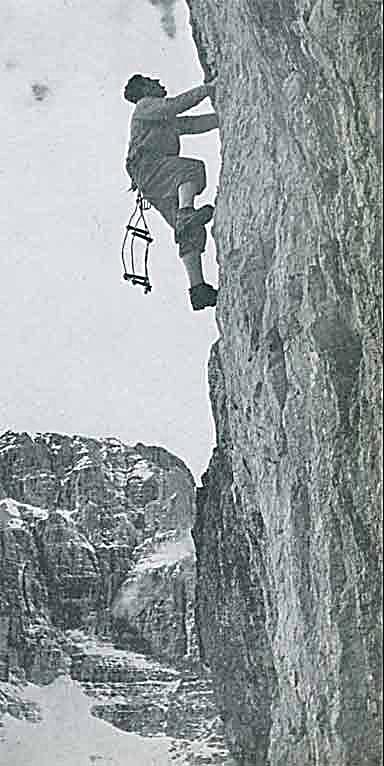

Cesare Maestri (foto Pedrotti) |

|

CUT

IT OFF,

CUT IT OFF – AT LEAST

YOU'LL MAKE IT!

by Dino Buzzati

This is the story of one of the scariest adventures which occurred

in the Dolomites. It happened last summer [1954, editor's note]

on the Campanile Basso in the Brenta Group, thanks to its marvellously

slender architecture and the difficulty of the many climbing

routes one of the finest peaks in the region.

It is astonishing from each side, and from each side it has

been attacked and conquered. There is not one wall, edge corner,

crack or cliff left where men haven’t hammered in their

pitons. The common climbing route, a 4th degree-route, is already

a pretty respectable climb. All the others are rather difficult.

Some of them reach the highest level of the possible, that is

the 6th grade.

As a matter of fact, the vertiginous itinerary traced by Marco

Franceschini and Stenico, on the North-Western edge of the so-called

Spallone (big shoulder) of the Campanile, is also a 6th grade.

It is an extremely impressive yellow pillar, jumping from the

gravels for 370 metres and stretching out over terrible precipices.

Cesare Maestri, together with his friend Luciano Eccher, age

26, wanted to climb it again, two months ago.

Even though it was extremely difficult, the enterprise was not

too preoccupying for Maestri, who had done even worse one-man

climbs, bravely and prodigiously carried out with refined acrobatics.

As to Eccher, he was a perfectly matched climbing mate for Maestri.

Even though they diverted from the original route and even met

some bigger obstacles, the two climbers brilliantly got over

the first 170 metres, which were the hardest. Towards evening,

Maestri, after an extremely delicate traverse right on the edge

of a scary cliff, finally got to a small secure ledge. There

were still 200 metres left, and luckily much less difficult

than the ones already covered. The victory, so to speak, was

already at hand. Thank God, as the night was already approaching

and it had also started to snow. Maestri anchored three pins

into the rock, attached them to the rope and then told his mate

to join him.

Eccher carried out the traverse, and almost reached the ledge.

Maestri saw his head, as he was controlling the rope, and thought

his friend was already safe, when it suddenly happened.

Luciano was smiling at me – tells Maestri – but

all of a sudden he made a funny face, as if he was annoyed for

some reason, then he disappeared below.”

In the most difficult points, where pins are missing, and in

particular on the cliffs where the rock leans out from the mountain,

the climbers not only hammer in pitons in order to carry on,

but to the very same anchors they also attach hooks where they

can put their feet. Eccher was leaning on just such a ---- with

all his weight when the nail came loose. His hands did not have

sufficient grip. Luciano fell. Underneath, nothing but emptiness.

The ledge was the edge of a roof that was jutting out for a

few metres. Eccher is all but a fat man, but nobody can take

away his 70 kilos. The pull was so hard that the steel spikes

broke, a first one, then a second one just above the hook and

then again a third one, just the very one Maestri was securing.

With the three pins gone (two were still left above the ledge,

but that was where the rope-head had been attached, the one

on Maestri's side) the entire weight of the body propelled into

the emptiness bore down onto the shoulders and the arms of the

guide. It was a tremendous pull. Maestri remained literally

doubled up and smashed his face against the rocks.

In spite of the pain, Maestri held on with all his strength.

Contorted almost upside down on the lofty ledge, half-blinded

by the blood gushing from the wounded forehead, the arms frantically

holding the rope, Maestri felt absolutely lost for a few seconds.

Then, a bit later, he started recovering little by little.

“Luciano, Luciano, how's it going?”

“It's alright, alright.” The invisible fellow mate

answered from underneath, with an extraordinary sense of humour.

“Are you down much?” “It must be at least

5 metres” - “Can you touch the rock?” “I

can't. It's too far away”, “Well then, try and climb

with your arms. Can you do it?” “I’ll try”.

Eccher tried, but the enterprise was simply improbable, with

such a thin rope and after that tremendous pull. He managed

to lift himself up a few metres but then his hands gave. Down

again. Maestri, laying in that absurd position, tried everything

in order to bear the second pull. Unfortunately a good piece

of rope slipped out of his hands.

“Luciano! Luciano!” “Don’t worry! I

simply can't make it with the sole help of my arms” -

“How far are you down now?” “It must be 10

metres by now”.

A long silence among the wailing of the wind. The snow was coming

down thicker and thicker. Then Maestri's voice: “Luciano,

I am afraid I can't hold on anymore” - “Cesare,

he answered, cut off the rope so that at least you'll survive!”

“No way, thought Maestri, not even in a million years!”

With a supreme effort he managed to lift himself up a bit, so

that he could kneel.

“Cesare! Cesare!” “Yes?” “Try

and let me down till the rope ends. Maybe I can then touch the

rocks” (it was just an illusion). “Wait! I'm trying”.

Was it because Maestri moved the foot under which the rope was

trapped? Was it because his hands couldn't bear it? What happened

was that at a certain point he just could not hold on anymore.

He heard the hissing sound of the rope running over the ledge

at a furious speed, an irresistible force was drawing him into

the abyss. He looked at the two remaining pins with their two

karabiners to which the rope was attached. Would it hold?

Then came the hook. The rope stretched agonizingly, in fits

and starts.

The two pins curved as if they were made of butter, for a fraction

of a second they seemed to shoot out of the crack they were

anchored in. “I'm gonna fly, too.” Thought Maestri,

but the pins held by a miracle.

Underneath, Eccher had completed his third bad fall, this time

until the rope ended, that meant a dive of a good 20 metres.

While falling he looked up. He felt the rope savagely tightening

on his hips. He bounced up 3 metres at least.

“It's impossible. The pins won't hold”, he thought

“now I’ll see Maestri shooting out: we will smash

together”. Then an unbearable silence. Eccher slowly started

to spin. They called each other, trying to speak. But, at such

a long distance, over 30 metres – it was too difficult.

In the meantime, darkness had fallen.

Maestri, no longer bearing the load of his mate, who was now

sustained by the belays and karabiners, eventually stood up

and assessed the situation. Lifting up Eccher with his bare

arms was out of the question. The sole possibility was to take

the easiest route down by himself, to try and get help. Could

he do it on time? And with his life hanging on a rope, would

Eccher resist? In similar situations, more than one mountaineer

had choked to death. Thank God Eccher was a level-headed man

and an optimist by nature. Instead of panicking, he managed

to make his situation less uncomfortable. He passed a hook around

his waist so that he could lean his back on it. He attached

another two hooks to the rope so that he could rest his legs

and assume a sitting position. Then he told himself: “If

Maestri goes looking for help, there's no need to worry”.

It was still snowing. Maestri freed himself from the rope, shouted

"Goodbye" to Eccher, and started climbing. How he

managed, in that darkness, to climb over 200 metres of a good

5th grade, still remains a mystery.

Once he had reached the shoulder of the mountain, he rounded

the Campanil Basso on the large ledge ironically called "stradone

provinciale" (county highway). He was about to go along

the usual route when, overlooking the South wall, he spotted

a light coming towards him on the little path that led to the

start of the climb. He called out. It was his brother Carlo

who, worried about his delay, had climbed up from the Tosa hut.

“Run down to the hut – shouted Maestri – call

as many people as you can with all the ropes available. But

before doing so, go under the edge of the mountain over there

and tell Luciano that the rescue squad is coming. Tell him to

cheer up!”

What he feared the most was that his friend would be overcome

by fatigue and discouragement, in that case he would be lost.

There was nothing left to do but wait. Maestri spotted a sufficiently

protected hole on the ledge and – as a wonderful example

of self-control – he managed to have a good sleep. That

was the wisest thing to do after what he had suffered and on

account of what he would still have to suffer.

At 2,30 a.m. the guides Bruno and Catullo Detassis and Giulio

della Giacoma along with three good rock-climbers, Mario Fabbri

from Trento, Dado Morandi and a third one from Rome –

were on the "stradone provinciale". In the uncertain

light of electric torches, from the summit of the mountain shoulder,

Maestri, Catullo Detassis and Morandi were lowered down for

110 metres. With double ropes, Maestri and Detassis lowered

themselves further down, above the ledge. They hammered a good

quantity of anchors in the rock and immediately lowered two

other ropes down to Eccher. Thanks to these ropes and alternately

pulling them, they started lifting him up. At each pull they

gained 20 centimetres.

The lifting lasted three hours and a half. At 9 in the morning,

Eccher eventually touched the ledge. He was as pale as death,

but still in a good condition. “It's kind of weird putting

your feet on the ground again”. He had remained hanging

in the emptiness, in his shirt-sleeves, in awful weather, for

precisely 13 hours.

From: Cronache Terrestri, in "Corriere

della Sera", 1954

|