|

A walk among lakes and woods in the company of a precious guide,

symbol of the safeguarding of places, told by an affectionate connoisseur

of Nature in this area.

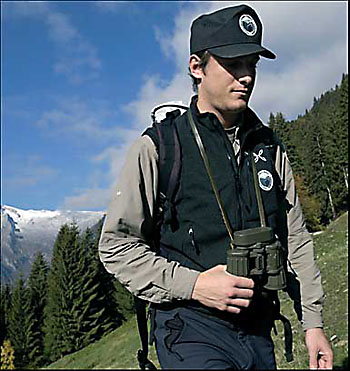

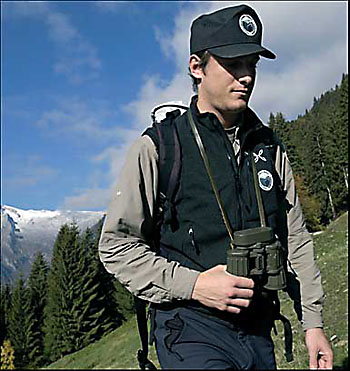

Park-guards working in Adamello Brenta

Lago di Cornisello

(foto Daniele Pellegrino)

|

|

AT THE LAKES OF CORNISELLO

WE OWE PARK GUARDS

A LOT

by Manuela Stefani

The sun is shining over Val Rendena making everything

glow of a beautiful brilliance. Quiet and massive, the two natural

bulwarks, Presanella-Adamello and the Brenta

Dolomites, towering from above, are dressing up with lights and

a fairy-tale charm as gigantic castles made of stone. The deep

green of the forests lights up with golden reflections and it

illuminates the mirrors over a thousand lakes, tinged with every

shade of blue.

The more and less known valleys still continue echoeing of rumbling

water, which roars and gurgles alternatively: the wild Nambrone

valley, the isolated Val di Borzago, the

well-known Val di Genova, the solitary Val di Fumo, while bunches

of locals and tourists keep pouring into the villages’ streets

and alleys. Nothing in the world would make them renounce to the

extraordinary show of a blue sky over their heads and the pleasant

warmth of the sun

that heats up their skin and bones.

Bulwark of winter and summer tourism, thanks to its “capitals”,

Madonna di Campiglio and Pinzolo, and to the less mundane, but

surely more suggestive villages, crowed

both in summertime and wintertime, loved by skiers and escursionists,

attended equally by Italians and foreigners, Val Rendenais, as

a matter of fact, a place which nature has given a lot.

A beauty that needs to be safeguarded.

In order to safeguard an heritage of such value, Val Rendena has

become part of what is the biggest natural park in Trentino, i.e.

Parco Adamello-Brenta. 620 square kilometres protected and supervised

by a small army of nature-friends: the park guards. Just a few

more than ten people: not many, if you consider the vastity of

the area, the human presence, both residential and touristic,

over which they have to watch.

Michele Zeni, age 26, is one among the yougest guards.

He chose his job already when he was 13, because that was exactly

what his father was doing. From that age, as a matter of fact,

his father had been teaching him to love

mountains and the place he was growing up in.

He is taking us out on the excursion.

Direction: lakes of Cornisello, two small communicating basins,

at the top of Val Nambrone. We are lucky having him with us: Michele

is a pleasant mate and a true mine of

information.

“The vegetation is abundant and varied: willows, birches,

sorbs, laburnums, elders, and larches, which have always represented

the richness of these valleys. Up high, there are the fir trees.

Here they take the typical column shape: the long winters, the

bitter cold and the overload of snow makes the longest branches

break. To this process, nature has found a solution”. Summer

rhododendron cushions

colour the slopes which are cluttered, in Val Nambrone, of stonemade

panettoni, usually smooth and rounded: “they are called

montonate rocks” – says Michele.

“The glaciers have eroded and smoothed them down completely.

During the autumn, when you can spot around here the capercaillie,

the rarer black grouse and the mountain hazel hen, when the days

are clear from dawn to dusk, the mountains are quiet and the animals

come out surely more often.

The real eagles fly in the sky. The deers change the colour of

their mantle, which is reddish during the summer, and fades to

brownish in the autumn, getting also longer.

The Alpine chamoises do the same: they become darker when the

cold comes.”

Bunches of volunteers and workers are looking after mountain paths

and pastures. They take away the thistles from the fields while

the paths are always kept clean: “the

slopes tend to be quite instable and dangerous. For this reason,

we move rocks, we force back the trees from an exuberant growing,

and we protect landslide risk areas

witht the help of special nets”, our guide informs us.

The water is abundant in Val Nambrone, a totally different situation

than in the more arid Val Brenta, “it is thanks to the impermeability

of the rocks that we have a lot of superficial water: the glaciers

– as a matter of fact – when melting, form lakes and

streams that cannot filter into the underground as it happens

instead in the Dolomites”, says

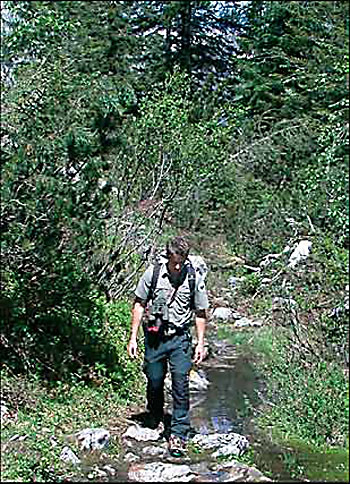

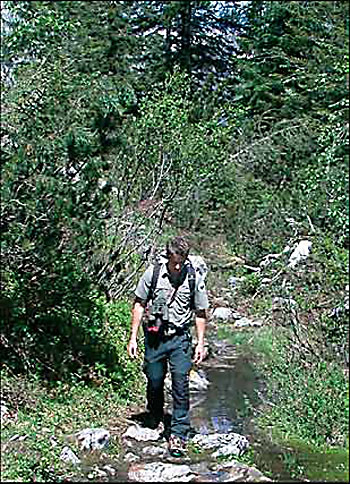

again Michele. You walk nicely in Val Nambrone: the hiking is

not difficult at all, the spectacular places fill your eyes and

soul and the company of a parkguard enriches the mind. So, pleasantly,

we get to the lakes of Cornisello. The water is icy and opaque

on account of the glaciers

nearby and as the result of the carrying of sedimentary material

downhill.

“Here lives the alpine char, an endemism which has adapted

itself to live in this climate, extremely prohibitive

for most kind of fish, – explains young Zeni. – Unfortunately,

a few years back, before the supervision

of the Park, there have been introduced in these very waters the

iridea trouts, coming from North America, very much appreciated

by sporting fishers. Unfortunately, they have created problems

to the more fragile chars and some kind of imbalance to the ecosystem”.

The way back flows more rapidly than the way out: as we descend,

we make the effort of fixing, in our mind and in our eyes, the

fragments of the miracle of perfection represented by nature in

this peculiar corner of the world, not that far away from our

home. Will it remain untouched

like it is today for future generations? To guarantee its preservation

as it is, young Zeni and others like him are doing their best.

We feel we owe them a lot.

Manuela Stefani, is senior editor

of the monthly magazine Airone, journalist and writer, and has

recently published for Mondadori the novel La casa degli ulivi.

|