THE SILENCE OF THE SUMMITS

Sonia Sbolzani

“I am observing people spending their Sunday in the woods or in the snow.

Bright coloured clothing, absent and fast pace. And then cars, lights, motor sleighs…

Nature has a thousand eyes, the wood is aware of something foreign or out of place and it shuts itself, it freezes…

For those able to listen, to smell, the wood communicates with a thousand signals and marks:

the first snow has a different scent than the last one,

the soil tells by its perfume if it is ready for the seed…”

(M. Rigoni Stern)

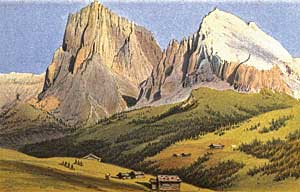

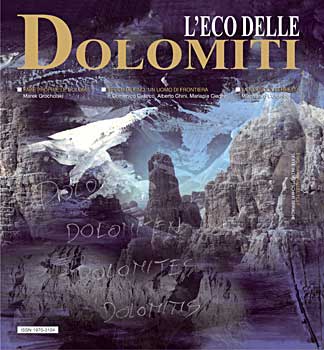

In the beginning it was only a geological phenomenon, that one of a sea that becomes pale pink rock. In fact, for scientists of the late 18th century the Dolomites were above all the spectacular mountains of dolomia (calcium and magnesium carbonate), not to be confused with the common limestone. The French geologist Dieudonné de Dolomieu had this intuition travelling through Bozen in summer 1789. The original name “Venetian Alps” was nevertheless, only replaced by the new one after 1864 when Josiah Gilbert and George Churchill, a painter and a botanic respectively, published in London “The Dolomite Mountains” – a journey report. Discovering them again today, we cannot avoid reflecting and contemplating once more these solitary and grand peaks, bristling with picturesque spires and dizzy towers, dominated by a paradoxically idyllic silence. Their horizon limits the view, like in Infinito by Leopardi, but not the mind that flies over the “hedge” in “endless spaces and supernatural silence, and extremely profound quiet”. In the beginning it was only a geological phenomenon, that one of a sea that becomes pale pink rock. In fact, for scientists of the late 18th century the Dolomites were above all the spectacular mountains of dolomia (calcium and magnesium carbonate), not to be confused with the common limestone. The French geologist Dieudonné de Dolomieu had this intuition travelling through Bozen in summer 1789. The original name “Venetian Alps” was nevertheless, only replaced by the new one after 1864 when Josiah Gilbert and George Churchill, a painter and a botanic respectively, published in London “The Dolomite Mountains” – a journey report. Discovering them again today, we cannot avoid reflecting and contemplating once more these solitary and grand peaks, bristling with picturesque spires and dizzy towers, dominated by a paradoxically idyllic silence. Their horizon limits the view, like in Infinito by Leopardi, but not the mind that flies over the “hedge” in “endless spaces and supernatural silence, and extremely profound quiet”.

However, silence is a one to one relationship. It interrupts the background noise of a world that has lost its essence and has suffocated the minds transforming quiet into emptiness and negation (even conceiving the “silence of God” in order not to admit the inability of mankind to be confronted with the open door to the abyss), instead of converting quiet into a place where the new “word” can sprout in conscience and freedom. However, silence is a one to one relationship. It interrupts the background noise of a world that has lost its essence and has suffocated the minds transforming quiet into emptiness and negation (even conceiving the “silence of God” in order not to admit the inability of mankind to be confronted with the open door to the abyss), instead of converting quiet into a place where the new “word” can sprout in conscience and freedom.

Of the alpinist that climbs a mountain it is usually said that he “conquers” it. Really, he is simply a visitor and he very well knows it. Summits do not permit any domination over them but they willingly accept a dialog where worlds are pauses. Mountains continually mark a divine separation and claim their surreal prone dimension with signals that our sensibility is obliged to recognise.

Tolstoj realised it perfectly when he wrote: “He suddenly saw… candid masses with their delicate outlines and the bizarre and clean aerial line of their peaks and of the distant sky. And when he understood the distance between himself and the mountain and the sky, the huge grandeur of the mountains, and when he realised the incommensurability of this beauty he was scared fearing it might have been a vision, a dream…”.

On the occasion of his stay in the Dolomites in 1913 with the poet Rainer Maria Rilke, Sigmund Freud wrote that the poet “admired the beauty of the surrounding nature but felt no joy. The thought that all that beauty was doomed to perish disturbed him”. On the other hand, persuaded by looking at the Tre cime di Lavaredo Freud understood that the fragility of beauty does not imply a loss of its value - far from it – it increases its worth! He declared: “The worth of beauty is determined only by its meaning for our vital feelings, it does not need to survive our feelings and therefore, it is independent from the absolute temporal duration”. On the occasion of his stay in the Dolomites in 1913 with the poet Rainer Maria Rilke, Sigmund Freud wrote that the poet “admired the beauty of the surrounding nature but felt no joy. The thought that all that beauty was doomed to perish disturbed him”. On the other hand, persuaded by looking at the Tre cime di Lavaredo Freud understood that the fragility of beauty does not imply a loss of its value - far from it – it increases its worth! He declared: “The worth of beauty is determined only by its meaning for our vital feelings, it does not need to survive our feelings and therefore, it is independent from the absolute temporal duration”.

Mountains are the innervate bones of the Earth, a kind of Gaia’s connective tissue, the living planet, but in constant dissolution minute after minute. No other organism is more “aware” of it than our Dolomites that with their progressive crumbling are witnessing the flow of time towards an end that will be a rebirth. Perhaps.

Silence suits the Dolomites like it fits the desert that in a way represents the Dolomites alter ego. Silence that is not broken by natural noises and sounds, but that interrupts the solitude of the sky and of the rare visitors. The great violoncellist Mario Brunello, protagonist of the cultural summer months in Trentino Alto Adige with the original event Suoni delle Dolomiti, has declared “The silence that the mountain can give is a vast silence that swallows any sounds. In order to face it one must search for sounds able to cross the deepest space…There is a big analogy between the beauty of the Brenta’s group and what I consider a massif of music”. Silence suits the Dolomites like it fits the desert that in a way represents the Dolomites alter ego. Silence that is not broken by natural noises and sounds, but that interrupts the solitude of the sky and of the rare visitors. The great violoncellist Mario Brunello, protagonist of the cultural summer months in Trentino Alto Adige with the original event Suoni delle Dolomiti, has declared “The silence that the mountain can give is a vast silence that swallows any sounds. In order to face it one must search for sounds able to cross the deepest space…There is a big analogy between the beauty of the Brenta’s group and what I consider a massif of music”.

Anyone who has had the fortune to reach the high altitude has certainly felt this way, as shown to be true by the fantastic words of a great mountaineer, Walter Bonatti: “Since leaving the valley we have not seen or heard any human being however, we do not feel lonely at all. The great mountain that we are striving hard to climb is very much alive. Maybe it is more alive now than in the summer, and we realise it thanks to the joyful and sometimes even loud voice of the torrents, the water falls, the chirping of the birds, the far away whistle of the marmot and the buzzing of a thousand insects attracted up here by fragrant flowers “.

Ascending to the summit one continually discovers flavours, sounds and colours until dusk when everything rests and melts into pure lyric poetry: “Down in the valley it is night. Where earlier on villages in the distance were to be seen, now small trembling lights, that break here and there the black wavy expanse of the surrounding mountains, have been lit. This is the most nostalgic time in the mountains, made up of alternating intimate memories and reinforced by anxiety and uncertainty for the climbing that awaits us”. Ascending to the summit one continually discovers flavours, sounds and colours until dusk when everything rests and melts into pure lyric poetry: “Down in the valley it is night. Where earlier on villages in the distance were to be seen, now small trembling lights, that break here and there the black wavy expanse of the surrounding mountains, have been lit. This is the most nostalgic time in the mountains, made up of alternating intimate memories and reinforced by anxiety and uncertainty for the climbing that awaits us”.

And in the starry silence up there everything seems to have a deeper meaning and the most profound thoughts sprout, the same thoughts that have made the poet Walt Whitman write: “… that summit is the Buddha’s mind, and that is Jesus prayer, and this is Plato’s dream, and that one is Dante’s melody, and this is Kant and that is Newton, and this is Milton and this is Shakespeare, and this is the hope of the Mother Church…”

In fact, like in a church one should enter the templum of the Dolomites “with light and steady pace” writer Mario Rigoni Stern has stated. He has also declared: “The Alps are made of ice, cold and hostile; to be faced with force. The Dolomites are snow, beauty, compliant with those who know and respect them”.

Mountains are all this, and all this they can offer us if we respectfully continue to consider them a dream. In conclusion, hence, a bright quotation by Tolstoj: He thought that the mountains and the clouds looked exactly the same, and that the particular beauty of the mountains covered in snow… was a dream as pleasant as music by Bach or the love of a woman…” Mountains are all this, and all this they can offer us if we respectfully continue to consider them a dream. In conclusion, hence, a bright quotation by Tolstoj: He thought that the mountains and the clouds looked exactly the same, and that the particular beauty of the mountains covered in snow… was a dream as pleasant as music by Bach or the love of a woman…”

Let us listen in silence to the Dolomites and we will see them like we never have, with the astonishment that makes us world’s connoisseurs ensuring us the space of the truth that reduces our fatigue of life.

|

NUMBER 10

NUMBER 10

NUMBER 10

NUMBER 10