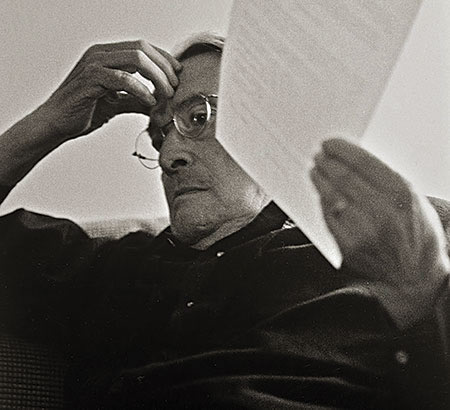

THE GREAT MASTER

Memoire of Luigi Meneghello 5 years after his death

Sonia Sbolzani

Five years ago, Luigi Meneghello, one of the most important Italian writers of the twentieth century, died in Thiene. I loved his novels - from “Libera Nos a malo” to “The Small Masters”, from “Pomo pero” to “Il dispatrio” - as much as the intense production of essays and journalism that ranged over the most disparate topics, focusing in particularly on the events of the last war, in which he had participated as a partisan fighter in the mountains of Veneto. And Meneghello dedicated passionate pages to those mountains, pages full of respect and poetry.

The Dolomites in particular, not only those of Belluno, but also those of Trentino, were always in his heart, and in this regard I want to report what he wrote about the Val Rendena and its surroundings in the “Cards”, long-forgotten manuscripts that were eventually published, partly before and partly after his death: it is a series that provides evidence of his attention and almost “childish” sensitivity to little things, small details of the provincial and rural life that had always fascinated him, as he said affectionately, especially in the “Libera Nos a Malo”, considered his masterpiece.

Here are his words: “In Val Rendena once, when boys playing with water made it trickle in the backyard or in the kitchen, the mothers did not say (in dialect of course) “Hai fatto un Sarca!”, but “Hai fatto una Sarca!”, making the river grammatically feminine. The masculine identity of the river is now the official one, but the other is, or was, the authentic form. I know this by direct certification, from a young mountaineer friend from Pinzolo in the 1940s. Why do I mention it? Because a random appearance of the name of the river brought it all back to me intact, as if projected up from the deep, the living kernel of a remote experience.

The Sarca ... I knew it in such a brilliant mood, but then let it go and bury itself… the Val Rendena and Pinzolo and St. Vigil, and the enchanted realm of Val Genova, and the terraces of the great mountains, Carè Alto, Adamello and the Brenta Group. I was very much alive and briefly (without knowing it) unusually happy there in that last, abstract week of July, 1942, while in my home, my own country, my grandmother died, a very devoted woman, worthy of heaven, but electrified at the end with the anxiety of having to leave her life to go away. Returning from our “Adamello” expedition (a long, carefree return trip, three friends on bikes) we saw from afar that the austere front door, ash and faded blue, was closed, and there was displayed the inscription outlined in black that told us, before reading it, that your grandmother Esterina was dead. What I felt was not manifest pain, but a kind of daze, like a blow on the head that before starting to hurt gives a curious sense of unreality. Then there washed over me (I was just twenty) a small Sarca of existential dismay: I knocked with the brass knocker, I opened, I went in.”

In this passage there is all the anti-rhetoric and polished sentimental realism of Meneghello, a highly cultivated man who still loved to speak in the fervent dialect of his childhood in the Vicenza area, something which he used handfuls of to “baste” his novels (always full of autobiographical points), explaining his “mission” as a writer like this: “I was forced to pay attention to everything, every single date, time of day, locations, distances, words, gestures, individual shots ”. So that nothing and no one who shared the journey of life with him could ever evaporate from the prism of memory... which is the means by which you conquer your identity, or the sense that gives value to life. A sense that for Meneghello is motivated by action and is not intended as an ultimate truth. In him, in fact, the memory works in silence before becoming the narrator and re-knotting the threads of memories that save from oblivion an experience of micro-events and micro-characters, which in the end turn out to be fundamental pieces of the mosaic of a macro-history.

Luigi Meneghello was born in Malo in 1922 and cultivated literary studies since adolescence (taking his high school diploma at the age of just 16), then approaching philosophy through university studies. Having entered the Action Party in the fascist period, he participated in the partisan struggle. After the war, he moved to England to teach, founding the faculty of Italian literature at Reading, and for decades divided his life between Veneto and Great Britain, eventually returning to his homeland permanently in 2000, following the death of his beloved wife (A Jewish Yugoslav of Hungarian language, who in her youth had lived through the experience of deportation to Auschwitz). The passion for teaching children accompanied him throughout his life, and to clarify his concept of education, he said in “Italian Flowers”: “There stood among the desks a boy with red hair, melancholy and courteous, who began to reproach the panel to have overlooked the most important aspect of education, the floral. We are flowerpots he said. You should cultivate us gently, make us flower.” Some important theatrical works have also been made on the basis of the works of Meneghello (Gabriele Vacis, Marco Paolini) and also films (a delicious transposition of “Little Teachers” by director Daniele Luchetti), underlining the strong communicative value of his narrative. Great masters like him will never die.