|

|

A symbolic mountain: the Campanile Basso

Although only a minute percentage of the Earth’s mountain terrain, the Dolomites possess a fascination without equal. None other than Reinhold Messner wrote in the introduction to one of his books, “If I had to decide between all the mountain ranges, I would choose the Dolomites”.

One of the main attractions of the Dolomite range is the infinite variety of shapes you find there; and even though it does not excel in terms of height (the highest peak is Marmolada which, at 3342 metres, is lower than hundreds of Alpine summits), we are astonished by the number of different outlines, which change in surprising ways as our point of view moves, or as the daylight changes.

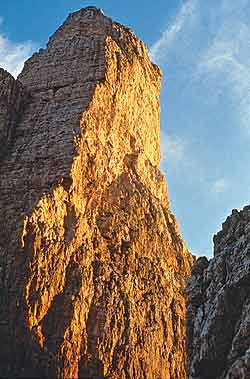

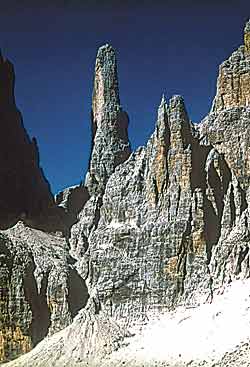

Above all we are fascinated how they soar, apparently against the laws of physics: all those columns, obelisks, turrets, belfries and steeples which stand out in the various chains: the Campanile di Val Montanaia in the Friulan Dolomites, the Gusela del Vescovà in the Bellunese Dolomites, the Torre di Pisa in the Latemar Range, the Torre Berger at the summit of the Val de Mezdì in the Sella plateau. However, none of these jagged peaks bears comparison with the Campanile Basso, which for its impudent elegance might be voted the symbol for Trentino.

The bare facts state that the Campanile Basso (still called, on some German maps, “The Spire of Brenta”) is a jagged calcareous rock, more or less square in shape, forming part of the central Brenta Range. It finds itself wedged in a kind of notch between the Brenta Alta and the Campanile Alto; “escorted” by a sharp pinnacle beside it known as “The Sentinel”. It is 2877 metres high, sixty metres less than its “big brother”.

Today the Campanile Basso no longer has any secrets to hide: all its walls have been climbed in every possible way, in all seasons, by day and by night and in all atmospheric conditions, by thousands of people. Walking along the paths in the high Val Brenta, just look upwards for a glimpse of the multicoloured ropes as they rehearse, for the nth time, the same old routes on holds now worn with use.

But once it was anything but easy, as can be imagined by climbers’ awe when still it was considered unclimbable. We must also remember the limitations of the equipment available at the time.

The first person who believed it to be humanly possible was Carlo Garbari, one of the finest Trentine climbers of the late 19th century. Accompanied by the guide Antonio Tavernaro and the porter Nino Pooli, they spent one night in the Tosa refuge (now an annexe of the Pedrotti). Then, at eight in the morning on 12th August 1897, they reached the mouth of the Campanile Basso on the assault of the east wall: an almost sheer drop of 260 metres. The moving report of this attempt is described in the highly recommendable book “Il Campanile Basso – Story of a Mountain”, by Marino Stenico and Gino Callin, (Pub. Manfredi, 1975). With unheard-of difficulties, the three men climbed using minimum holds, conquering the ledge now known as the “provincial highway” and reaching a balcony where there was barely room for their six feet. They were exhausted after ten hours on the rock-face when, on coming across a smooth, overhanging wall, they decided to give up. Before descending, they wedged a bottle under a boulder containing the message: “Who will find this message? I wish him the best of luck!” In fact, although they could not then know, they had overcome the most difficult part of the climb with ease and were less than twenty metres from the summit. The solution to the enigma lay a few metres away from that smooth wall; and it was left for others to solve it just two years later.

The mass media of those times were not as rapid and diffused as they are now. So when Otto Ampferer and Karl Berger - two Innsbruck students who had made a name for themselves already as climbers - reached the Tosa refuge two years later, while attempting to scale the “Basso”, they had no idea about the previous attempt. So when, on the 16th August, they discovered a hammer left by Garbari, Tavernaro and Pooli, it was such a blow that they nearly gave up. For even if they had reached the top, they would not have been the first to do so. But then dejection was replaced by euphoria when they dug out, from beneath a pile of stones made in the shape of a man, the bottle with its message. The summit had not been reached! Then, when Ampferer stepped down behind some rocks, he noticed a small sloping ledge. Although exposed, it was crossable and appeared to lead to the top. By now it was late afternoon, so they descended to the refuge; but two days later, on the historic day of 18th August 1899, they tried again. Despite a potentially fatal rock-fall, they reached the top of the jagged rock. In fact, it was a broad table, which was quite unexpected from what could be seen from down in the valley. They celebrated their conquest by banqueting on a tin of sardines, which they drained to the very last drop of oil.

There followed a long series of ascents, interrupted only by the two wars, using the same or other routes. Figures issued at the beginning of the 1980’s spoke of six thousand people having climbed the “Basso”, and by today that number will have more than doubled. Of the many feats of the most distinguished climbers of the 20th century, for which I again refer you to the above book, and also to “Il Gruppo di Brenta”, by Franco De Battaglia (Pub. Zanichelli, 1982), two in particular deserve to be mentioned.

5th August 1933: Bruno Detassis, then a young 23 year-old who would later create the Via delle Bocchette, was leaning on the door of the Tosa refuge, admiring with his friend Nello Mantovani the outline of the mountains against the starry sky, lit by a full moon. Nobody had yet thought of a night-time ascent. Probably all it needed was an exchange of glances, and then – at 10 in the evening - off they set towards the Bocca di Brenta and then on to the base of the Campanile. “As my eyes get used to the darkness, I begin to see the grips better. We speak as little as possible, not wishing to break the silence of the mountain. Higher up we find the Moon; a little further and we’re at the top… …Abseiling one by one, a rapid descent down the snowy slope and by four in the morning we’re back at Tosa”. This is the brief account of an exceptional feat.

4th August 1940: the number of ascents of Campanile Basso was about to reach the thousand mark and there were lots of climbers around the Bocca di Brenta, all waiting for the chance to be the fateful thousandth one to conquer the summit. After the return of the 997th rope, Gino Pisoni, one of the ablest guides in the Val Rendena, had a brilliant idea: he set off with four followers up to the first pitches on the wall. Then he sent them up two different routes. Now the cat was out of the bag: the two pairs were going to make the 998th and 999th ascents, so that Pisoni could make the thousandth one all by himself. There was a chorus of protest from the contenders below. Then Pisoni, with the comradeship normal among climbers, waited for his friends Paolo Graffer and Marcello Friedschen to reach him so all three could accomplish the feat. They recorded their achievement in the summit log by placing their signatures in a triangle. |