How many times had I heard his name in Cesare Maestri's story about Cerro Torre? Then, one day in the marquee at the Trento Film Festival, there he was standing right in front of me.

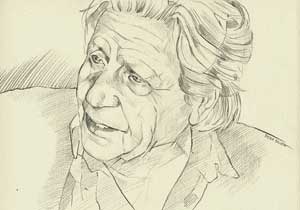

A small man with white hair, his face lined but serene and still able to smile; an old man who seems young when he talks about the mountains. He wears defective, built-up shoes that make him shuffle rather than walk. A friend of mine wanted to meet Cesarino -now just a few metres away- but lacked the courage to talk to him. So, although I had never seen Cesarino in the flesh, I took my friend by the arm and introduced them to each other. A year later, we met again at the festival. I was promoting my book and Cesarino was there for the showing of Patacorta (small feet), a documentary about his life directed by Elio Orlandi.

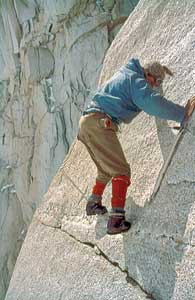

We spent three days together telling stories, recalling the past, our impressions, and climber's talk: the things that men looking for adventure carry with them -the jealousy and grudges- though the mountain passes and paths. I was touched by this small man's stories that he told so calmly, without illusions, yet passionately enough to bring tears to my eyes. Patacorta deeply moved me: it teaches us to face the vicissitudes of life with openness, obstinacy and passion for the mountain's open spaces and great adventures. At one point in the film we are told, "The mountain destroyed me…and yet it also saved me!" Cesarino Fava's story began at Malè in Val di Sole on 12th June 1920. He came from a family of twelve children and spent an adventurous youth in the mountains, skiing and taking part in the tests of skill and courage of childhood. At eighteen he went off to work at Brennero Station. During the war he was called up and spent five years as a private in the army. Then he got a job as an engineer on a ship sailing to Buenos Aires and settled there.  Here, on the Aconcagua, he went through a terrible experience that ended with the amputation of all the toes on both feet. Then in 1958 came his great adventure on the "The Impossible Mountain", Cerro Torre. Following this, at 58, he climbed Fitz Roy; and with two bivouacs, he returned to the Torre, the route to the south wall of Mercedario followed by the publication by CDA of his book "Patagonia, land of broken dreams" in 1999. He was a climber with a capital "C". For him, reaching the summit came second to respecting the mountain and all that goes with it in terms of integrity and regard for the rules. More than once he did his utmost to save a climber in difficulty, even when it meant he would not reach the top. His mountain was an experience of life that allowed him to appreciate every little human and natural phenomenon. From simple deeds, a flower's scent, an animal taken by surprise, an eagle overhead, to the breath of existence: all cherished as a divine gift, because all part of the same essence.

Here, on the Aconcagua, he went through a terrible experience that ended with the amputation of all the toes on both feet. Then in 1958 came his great adventure on the "The Impossible Mountain", Cerro Torre. Following this, at 58, he climbed Fitz Roy; and with two bivouacs, he returned to the Torre, the route to the south wall of Mercedario followed by the publication by CDA of his book "Patagonia, land of broken dreams" in 1999. He was a climber with a capital "C". For him, reaching the summit came second to respecting the mountain and all that goes with it in terms of integrity and regard for the rules. More than once he did his utmost to save a climber in difficulty, even when it meant he would not reach the top. His mountain was an experience of life that allowed him to appreciate every little human and natural phenomenon. From simple deeds, a flower's scent, an animal taken by surprise, an eagle overhead, to the breath of existence: all cherished as a divine gift, because all part of the same essence.

A year later, when we met again in Trento, Cesarino had the same smile and the same enthusiasm as ever. The Festival had just ended and we sat on a bench in the shade of some trees to talk about his life.

What was it like during your two years at the Brenner Pass?

Very hard, because it was my first time away from home. It was like going to the end of the earth, because Brenner was the most inhospitable place in Europe. In the winter of 1938-9 the temperature went down to minus 36 degrees and my bedroom wasn't heated. I used to get up at three o'clock in order to go to work at the station for an international freight company.

And what about your five years in the army?

Italy declared war on France in 1940 and I was posted to Val d'Aosta.

Then they sent me to Mentone, in France, where I was part of a detachment gathering information on the rolling stock in France. We used to bring perfume back to Italy from France and then took stockings to the French girls when we returned there. Then I was drafted to Croatia and some other places, finishing the war as a private, of which I am still proud today.

What made you board that ship?

After the war I started work on a farm, but there was no future in it. You couldn't even make ends meet. So I took a job as an engineer on a freighter. The ship was built for the outward journey only and there were all sorts on board: murderers, thieves, stowaways, people of the worst kind who wouldn't think twice about slitting your throat.

What impact did Argentina have on you?

What impact did Argentina have on you?

I couldn't believe my eyes. In 1952 Argentina was the land of milk and honey and the streets of Buenos Aires were paved with gold. In restaurants they brought you huge amounts of food, and you could live well for two weeks on a day's work. Meat was plentiful and there was a lot of waste. It was easy to find a job.

What gave you the idea of climbing the Acconcagua?

In Buenos Aires I met some Italians who, like me, loved the mountains. We set up an Argentinian branch of the C.A.I. and decided to climb the Acconcagua, the highest mountain outside the Himalayas.

How did the climb go?

We were used to rocky mountains, so a volcanic mountain covered in scree didn't scare us. We underestimated it. People had already been killed and the Puna, the icy wind in the central Andes, caused us a lot of trouble; but being Alpine climbers we were confident. Four of us set out; but at Plaza de Mulas two people fell ill so, after four days, we gave up. I myself had reached a height of 6900 metres, quite near the summit. I gave up because I wanted to reach the top with my friends.

When you tried to save the American climber Burdsall on the Acconcagua you ended up with your feet being amputated. What actually happened?

Two years later I was climbing again with Leonardo Rapicavoli. We reached the summit with Richard Burdsall, who had taken part in the K2 expedition in 1938. He was with someone from Mendoza who claimed to be a guide, but who left him when we reached the top. Burdsall was ill and I tried to get him down to a ditch where we had two sleeping bags. I lifted him onto my shoulders but I was exhausted and my legs gave way. So we bivouacked. After digging ourselves a hole, we spent a hellish night at minus 25 degrees. Suffering from ophthalmia and exhaustion, although we could hear a voice, we couldn't tell where it came from. We made a difficult descent to home base with frostbitten feet. Two months later they had to amputate all my toes.

What were those two years following the amputation like?

Fortunately I had saved some money. Also, that was when my brothers came to Argentina. I was desperate and close to suicide: I felt that my life had ended. Then I met a shoemaker from Veneto who understood my situation and offered to make me a pair of shoes. When I put them on, it seemed as if my feet had come back and I felt like climbing again.

In your book you say that, in life, we must keep up the struggle.

Yes, life is a continual struggle and the important thing is to understand this; but it would be unforgivable to think of living without a fight. You have to accept that it is an unavoidable part of life.

The passage "… to fade in a sweet painless nirvana!" is very good. What made you think of this?

The passage "… to fade in a sweet painless nirvana!" is very good. What made you think of this?

I had got together six friends to climb Cerro Cuerno, but in the end I was left on my own. I understood that they had dropped out because of my feet: they were worried about me and didn't want me to go. So I took my rucksack and went off alone. I went because I wasn't afraid of death and even if I'd fallen, disappeared for ever, perhaps it would have been a nice and painless way to go.

The Cerro Cuerno was your return to the mountains; but you also risked your life there.

Yes, once I reached the summit, I felt covered with glory, bursting with a joy which overcame me. I was living my life again and was ashamed of having thought about death: there were many people less fortunate than me confined to wheelchairs.

What did your experience at Torre mean to you?

Life! When I got back from Cerro Cuerno I wanted to do something big, something beautiful. Then, when I met some French people who had come back from Fitz Roy and they told me that the Torre was impossible, I decided to give it a go. I was cocky enough to think that nothing was impossible.

What were those long days like waiting in the fox-hole for Cesare and Egger to come back?

It was hard, waiting between hope and despair; but I was prepared for the worst. Anyone who thinks of taking the Maestri-Egger route must be prepared to die in the attempt.

What was Toni Egger like?

What was Toni Egger like?

He didn't laugh very much, but he wasn't a miserable type either. He had an English sense of humour, but was more serious than light-hearted. He was a real German! There was a certain feeling between us, perhaps because we had both been in the war and lived through danger. As a climber Egger was the best ice climber of his time. On ice he was at least ten years ahead of his time.

"Tragedy is not just part of mountaineering, but of everyday life"

Certainly, after the amputation I went around Buenos Aires on crutches. It was humiliating and I felt terribly alone among millions of people. I mean to say that we all die when our time comes, neither a minute sooner nor later. Death is a tragedy because it is the end of a principle.

Why do you regret the fact that Armando Aste, then an up-and-coming climber, wasn't at Cerro Torre?

Armando was very good indeed. If he had been with us on the first expedition, his stubbornness might not have carried us to the top. We would certainly have reached the "Torrete".

Is there a climber whose integrity and class have inspired you most?

Paul Preuss: I have always admired him very much. I was astonished when I read about his route on the Campanile Basso and how he had managed it. I also like what Eric Shipton wrote. I was never very keen on Comici, even though he was a very good climber.

In your book you often write about the rock as your great love, which overcomes all forms of rejection; and you wonder if this might be the essence and spirit of mountaineering.

In your book you often write about the rock as your great love, which overcomes all forms of rejection; and you wonder if this might be the essence and spirit of mountaineering.

Yes, if you can get to this point, it is beautiful. It has been a long time, but I still feel emotion when I think about the Torre, its walls and its peak. For me the Torre was like the Himalayas for the Nepalese: it was the symbol of spirituality. It was as though it had shown me the way to an even higher thing; and I did not want anybody to reach the peak.

Can you tell me about the time on Mercedario when you ate bacon and washed it down with your own urine?

My companion was stuck on a ledge and couldn't carry on. I was above, near to the summit, but I gave up and came down on hearing his cries for help. His boots had fallen off and he couldn't walk. I had to let him down along the wall using a forty metre rope, without pitons or an axe. After eight bivouacs I was at the end of my tether. I couldn't understand anything any more and went ahead on instinct. I was dehydrated and thought the end had come. After urinating into a flask, I added some snow and swallowed the lot. That's what saved us.

How did you feel when you fell thirty metres on Fitz Roy.

After several days on the wall we were exhausted. The freeze-dried food didn't work and our legs were finished. Luckily, on the ledge to the upper camp, I found a bag with some tins of sardines. I put them in a plastic bag and took two steps…into the void. I can't remember anything after that, but found myself in a bluish funnel surrounded by white and saw my body on the edge of a cleft, exactly as I was dressed. I had a broken leg, wounds and blood and then I thought: "Look how beautiful death is." I had had an out-of-body, near-death experience.

"Death is always close to us: to children, the young and the old. It is there, but is invisible. In the mountains it brushes against you and you can almost feel its breath." Can you explain this passage?

Yes, death is not a physical thing, but the end of a principle, and the silence and real dangers of the mountains bring it closer to you on certain occasions, as though it were part of your own body. Its breath is the breeze in the thundering sky, and the avalanche that rumbles towards you.

Your book is full of praise for the mother who was able to bring up ten children and work the fields, and for the moral and ethical values of your childhood.

My mother was a pillar of strength, a guide, and a star who represented security. I still feel remorse about the fact that, when I returned home on leave during the war, she lovingly polished my five pairs of shoes, even though I didn't want her to. It didn't seem right; but for her it was a duty. At home, affection consisted of practical things. I don't remember ever being hugged by my parents, and when I went off to Brenner there was only a "Bye-bye".

My mother was a pillar of strength, a guide, and a star who represented security. I still feel remorse about the fact that, when I returned home on leave during the war, she lovingly polished my five pairs of shoes, even though I didn't want her to. It didn't seem right; but for her it was a duty. At home, affection consisted of practical things. I don't remember ever being hugged by my parents, and when I went off to Brenner there was only a "Bye-bye".

How did you get by in Argentina?

I did a bit of everything: dishwashing, I ran a drinks stall and then I started up a chicken farm. Once, when I came back from an expedition, Armando Aste turned up at work when I had to send out twenty thousand chickens and didn't know how to manage it. My work-mates didn't want to work on their day off, so Armando, Mario Manica and the others in the group offered to help me out. We spent all night loading chickens in the rain.

Argentina was like a second home to you. What did it really mean to you?

The best years of my life. Our house was the reference point for all mountaineers planning to climb in the Andes, so we were always meeting people and organising adventures. I met my wife there, the daughter of people from Friuli. She has always helped and supported me. I have never felt like an emigrant, but an Italian living in Argentina who was always going on an expedition. In fact, I have been on 23 of them.

always meeting people and organising adventures. I met my wife there, the daughter of people from Friuli. She has always helped and supported me. I have never felt like an emigrant, but an Italian living in Argentina who was always going on an expedition. In fact, I have been on 23 of them.

I know that you read a lot. What do you like reading most of all?

The "Pensées" of Blaise Pascal, the greatest thinker of all time. This little book is the best of books, a guide to life and a book which contains everything.

What about the future?

I am writing a new book and I would like to climb again and go to the Himalayas, because I have never been there. I have plenty of dreams and don't have time to get bored.

By the time I left it was getting late. We said goodbye as people came and went. The light of the sunset playing on his long white hair made him seem like a young man. Then a puff of wind ruffled him, he smiled, and went off with that funny walk and delightful expression of his.