Professor Umberto Neuwirth was actually not a professor at all. He opened his surgery as a fresh graduate of medicine in a small village not far from Jojutla, directly next to the Emiliano Zapata museum, which also was not a museum, but a small room, dirty and dark despite all its windows, in which members of the local Communist People's Democratic organisation used to convene long ago. They are all dead now, and so the room came to be occupied by the local free thinkers, who used it to hold discussions and domino matches. The reason why the stocky – it was a type of stoutness which made it hard to distinguish whether it was obesity or the result of bodybuilding – professor opened his surgery just here was simple. On the basis of statistical almanacs and long-term surveys by an international health institution, he had calculated that the greatest number of injuries in the coming years would take place at this very location. It is possible that Professor Neuwirth erred in his calculations or the surveys were inaccurate, but the cranial fractures and compound fractures of upper and other limbs, which his luxuriously furnished surgery counted on the most, kept on failing to take place. So the professor spent most of his time in the museum, where he took part in long discussions on the state of the world with Pastor Emilio Rodrique Sanchez Stoppa. Their mutual understanding, one could even say a nearly perfect consensus, was disrupted by just one particular issue: that each of them talked about completely different things. The professor elaborated on his theories, which explained why it was just here, and not in some mountain village in Africa for instance, where an unbelievable number of injuries would have to take place any minute - injuries

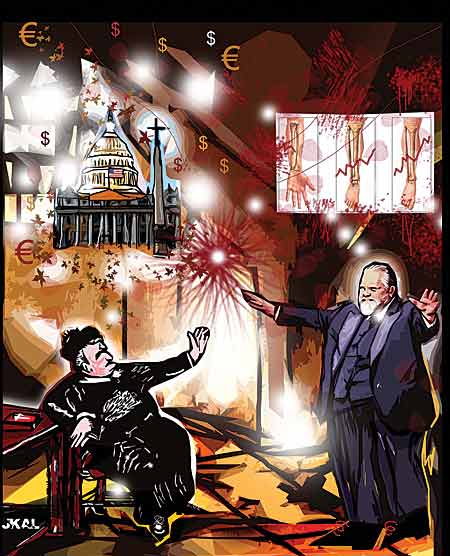

Professor Umberto Neuwirth was actually not a professor at all. He opened his surgery as a fresh graduate of medicine in a small village not far from Jojutla, directly next to the Emiliano Zapata museum, which also was not a museum, but a small room, dirty and dark despite all its windows, in which members of the local Communist People's Democratic organisation used to convene long ago. They are all dead now, and so the room came to be occupied by the local free thinkers, who used it to hold discussions and domino matches. The reason why the stocky – it was a type of stoutness which made it hard to distinguish whether it was obesity or the result of bodybuilding – professor opened his surgery just here was simple. On the basis of statistical almanacs and long-term surveys by an international health institution, he had calculated that the greatest number of injuries in the coming years would take place at this very location. It is possible that Professor Neuwirth erred in his calculations or the surveys were inaccurate, but the cranial fractures and compound fractures of upper and other limbs, which his luxuriously furnished surgery counted on the most, kept on failing to take place. So the professor spent most of his time in the museum, where he took part in long discussions on the state of the world with Pastor Emilio Rodrique Sanchez Stoppa. Their mutual understanding, one could even say a nearly perfect consensus, was disrupted by just one particular issue: that each of them talked about completely different things. The professor elaborated on his theories, which explained why it was just here, and not in some mountain village in Africa for instance, where an unbelievable number of injuries would have to take place any minute - injuries  which could only be healed by surgical intervention. He colourfully described the process of amputation and, at the other end of the spectrum, the various different ways of sewing limbs back on, methods of stopping internal haemorrhages with a single incision and the typology of operable boils. He enthusiastically expounded on how many stitches are needed to close what kind of wound. Don Emilio, in contrast, spoke of the depravity in the world, of the need for purification, the strongholds of heathendom and degeneration and the need for a radical course of action. He spoke of the needs of the soul and decried the body, especially the baring thereof. He furthermore raged against the expansiveness and greed of the Vatican, in which respect he likened the Vatican to Washington. He composed long letters in the Nahuatl language on how to put the world right and sent them, signed by Professor Neuwirth, unpaid to his own address. They were frequently returned back to him, apparently unopened.

which could only be healed by surgical intervention. He colourfully described the process of amputation and, at the other end of the spectrum, the various different ways of sewing limbs back on, methods of stopping internal haemorrhages with a single incision and the typology of operable boils. He enthusiastically expounded on how many stitches are needed to close what kind of wound. Don Emilio, in contrast, spoke of the depravity in the world, of the need for purification, the strongholds of heathendom and degeneration and the need for a radical course of action. He spoke of the needs of the soul and decried the body, especially the baring thereof. He furthermore raged against the expansiveness and greed of the Vatican, in which respect he likened the Vatican to Washington. He composed long letters in the Nahuatl language on how to put the world right and sent them, signed by Professor Neuwirth, unpaid to his own address. They were frequently returned back to him, apparently unopened.

(Readers who are impatiently waiting to find out when the subject of Christmas comes up, we ask you to bear with us for a couple more lines.)

Don Emilio scrupulously attended to his duties; the church which he took care of, with its garden enclosed by high walls, was also not far from the museum. The town square and marketplace separated the two. Behind the church, the village ended. Don Emilio, who, as we are not afraid to emphasise, really devoted himself to the fulfilment of his duties quite responsibly, never failed to serve holy mass during the first and second sowing festival, but the church calendar failed to include Christmas, and indeed all of December. How this came to be is hard to say. Don Emilio was intuitively aware of this hole in the church schedule and explained  this fact by saying that there were events which would first have to take place in order to fill it. So every year, he spent all of December and especially Christmas in prayer and contemplation in anticipation of the nascence of that, the son of God, as he called it himself, which would put the world and the church calendar in order. He always decorated the entire church carefully with banana leaves, strewed flowers about the garden and skilfully cut coloured papers from chocolate and cocoa into five-pointed stars similar to those he had seen in the museum.

this fact by saying that there were events which would first have to take place in order to fill it. So every year, he spent all of December and especially Christmas in prayer and contemplation in anticipation of the nascence of that, the son of God, as he called it himself, which would put the world and the church calendar in order. He always decorated the entire church carefully with banana leaves, strewed flowers about the garden and skilfully cut coloured papers from chocolate and cocoa into five-pointed stars similar to those he had seen in the museum.

But neither the coming of Christmas and the son of God, as Don Emilio dutifully termed it, nor an epidemic of bone fractures and operable diseases took place that year. Our heroes are both waiting it out until next year, together with the construction and opening of the first supermarket in the village, but we’re not going to get to that in our story.