| |

Shadows and fire. The colours oscillate between two poles in this alpine meadow, alongside the mountains. A pole of shadows, with the dark green of the forests of Swiss pine, silver fir and ash, but even more with the opaque range of the colours that can be seen on the slope in the shade, the damned face of all the mountains. This is certainly the wild territory of the shy bear, who goes about his way in a chlorophyll world of bushes, stern fir-wood forests, berry plants, abandoned carcasses and caves; it is the world of the first among hunters, with his thick shadowy fur that spreads from his primitive face into acid green and fragran t brown. t brown.

The fire pole dominates on the sunny side, when nothing can filter the vivid colours of the mountains, because no urban scene or untimely clouds of smoke can push them away, out of mad scorn, into the background. Like in Segantini’s paintings, it is then that the colour acquires slivers of fire; it sparks, it vibrates, it imposes its strength. It becomes a multi-headed snake. It is matter in freedom. In Val Nambrone, it climbs up along the granite like a beige, grey, emerald coloured hand, before being touched by the oxygen of the summits and evaporating into a cerulean blue; lower down it then creates some vegetable traces that sometimes sneak in between two masses of granite. Below Campiglio, where the bulky chalets are arranged in a funnel-like fashion and decorated with flowers, the fir woods are a fur lining to the steep slopes that lead to the Vallesinella waterfall. There the blue of the waterfall is so fast that it almost seems invisible.

Val Nambrone. Poles of light and shadows alternate. The colours circulate like that sand that gives a touch of turquoise to the rivers. In the pole of shadows, the violet hint of the blueberries moves, the berries are initially invisible, only then to be perceived all of a sudden, until we see nothing else. And again, fire, the grassland where the wheel of time goes around and around, the warm and shiny faces of the cows of Val Rendena who rummage through the nettles, around one of those shepherd’s huts that once belonged to noble country-folk. Higher up there is a series of lakes, the largest and furthest one is a deep blue colour, sometimes opaque. The smallest one on the other hand, is a transparent drop, curled up at the foot of the mountain that is reflected in it, in a frank and defined manner. The game of colours in the microcosm continues on the white road that leads back, the colour of talc and chalk (the sun is preparing its retreat), of spotted pebbles, black spots on white, until the whole countryside below finds its lonely shadow and the sky becomes a Prussian blue.

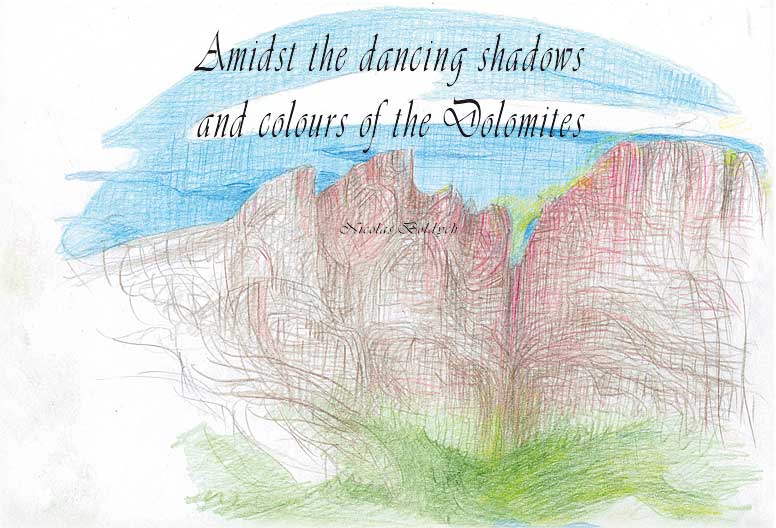

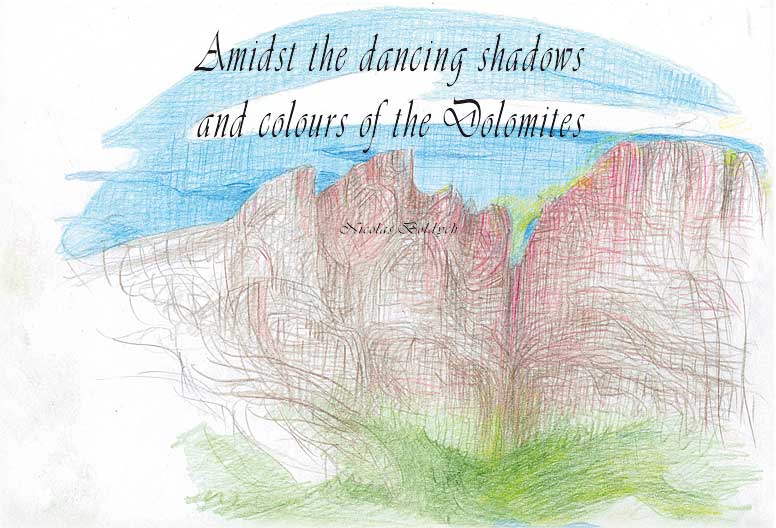

In the distance, all the colours that appeared during the day come together at the foot of the Brenta Dolomites, they then climb back up and in petrified strips they tie themselves around the vertical slope of the cliff without any cracks.

Because something happens, up there, amidst the towers and the steps, along the smooth and flaking facades, on the lunar plateaus. Reddish and fresh in the morning, the Dolomites become yellow at midday and acquire a greenish tint in the afternoon, as though they were invaded from their roots by the colours irradiated from the cones of the fir trees, until they acquire shades of indigo with strips of bright red in the evening time. They are soaked in light for the whole day, like submarine sponges and they irradiate that light like the corals that they were in the past.

Is there such a thing as Dolomite obscurity? Do they produce shadows like the other mountains, of sandstone, schist and granite? During this summer I doubt it, because the pale mountains do not bring their shadowy mass onto the nature that is the prisoner of these great porous walls, made of limestone and magnesium. They remain distant, like the Moon, which is ever-present yet constantly coloured with discretion. It is far away, silky, cold. And the mountains are far away, silky and cold. Their plasticity is clear, perfect and always moving. Is there such a thing as Dolomite obscurity? Do they produce shadows like the other mountains, of sandstone, schist and granite? During this summer I doubt it, because the pale mountains do not bring their shadowy mass onto the nature that is the prisoner of these great porous walls, made of limestone and magnesium. They remain distant, like the Moon, which is ever-present yet constantly coloured with discretion. It is far away, silky, cold. And the mountains are far away, silky and cold. Their plasticity is clear, perfect and always moving.

Looking back towards the past, I recall the mountains of the High Alps or of Isère in France, lonely winters. The shadow of the mountains is heavy and ruthless, the stone and inert mass are blended together; it is the time in which the mountain passively crushes what it had passively dominated up to that time with is oppressive shadow.

But during the summer nights the Dolomites continue to shine beneath the moon, coming back like a morning tide, brought back by the East that illuminates them. I catch a glimpse of transparent, translucent mountains as I go from Madonna di Campiglio to Pinzolo, along the winding road, at regular intervals I see their palpitating flesh appear furtively, unable to produce a shadow.

Farmer Cheval and the Dolomites

What do I see, what did I see looking at the Dolomites? Merlons, spires, pinnacles, towers, spurred arches, pointed arches; bell towers, domes, more towers, but also corals, sponges and shells, a thousand fragmentary and sedimentary things, that I could also have glimpsed on the facades of farmer Cheval’s building in Hauterives. Looking back, I think of the dream building and of farmer Cheval, a heroic artist who spent his life building his temple of nature, stone by stone (it would later be called the dream building), in the hills of Drôme, in France. The fact that he lived near the buttresses of the Alps undoubtedly inspired our hero, given that his building is a geo-archaeological accumulation, like the temple of Angkor or the Hindu temples of India. Vegetable is set alongside mineral, the sedimentation of the styles makes it almost a natural work of art, at the same time naive and sacred. The same goes for the Dolomites, had they seen it, they would have confirmed the farmer’s initial intuition, which was expressed on a marvellous pebble of the paths of Drôme, knowing that there is never anything forced in the magic of a mineral form, and that they only carry the memory of antediluvian eras, which were necessarily “genial”.

They are part of the petrified subconscious, the Parisian surrealists would have added, great admirers of the farmer.

The Bastiani fortress and the waltz The Bastiani fortress and the waltz

In the evening, under the light of the moon, I see an imaginary fortress in the Dolomites, between two worlds, Dino Buzzati’s Bastiani fortress of the “The Tartar Steppe”. I imagine the hordes of Cimbrians, Lombards, Bavarians who all witnessed the pale mountains rising up before them, illuminated by the light of the east, before flowing into the building that hid the backdrop of the sea from them, of Genoa, Venice or Ravenna; the majority of them passed through Val Rendena, at the foot of the Brenta mass. They were the last remainders of the moon before the full sun. They were the Tartars, the last reincarnations of whom were certainly the Austrian-Hungarian soldiers of 1915, who came to bring a white, lunar war to the deserts of the summits.

In a stube in Campiglio, after nightfall, near the indigo coloured Dolomites, I feel like I am in an Italian Austria-Hungary; I begin to digress, with the help of some Austrian beer: “Then the fortress was integrated into the Empire of the East, and the pale mountains linked the Italian peninsula to the so-called internal Ocean, which extended from Lorraine to Vojvodina and Galizia, once dominated by the Habsburgs of Vienna. One of the political and military hearts of Europe, it was then located in the mountains and Trentino was part of it, like the Sudetes or Transylvania. The mountains of Czech and Slovakian countries, the Italian Alps, the Carpathians, one by one the Habsburg Empire lost these tentacles that allowed it to spread through Europe, from Vienna. The empire had its last lunar queen with Sissi, then it disintegrated to the air of a waltz, a Radetzky march that can still be heard during the Habsburg carnival, at the end of July, in Madonna di Campiglio”.

Something of those Viennese dances remained, they are interwoven with harmony, pomp and stability, in the spectacle of the Dolomites of Brenta and Madonna di Campiglio.

And something of the Dolomites undoubtedly remained in Buzzati’s metaphysical and lunar stories, as in the idea of the Bastiani fortress.

Alpine huts

Val di Genova. The bottom of the Alpine valley has the atmosphere of a biblical desert. The anxiety that you happen to feel there is balanced by a sort of inebriation that rises up when the sound of the bells around the necks of the cows makes the silence even more profound. Solitude, poverty, sun: a rare blend: In middle ages, the owners of the precious Alpine huts had to be ruthless towards each other, like the shepherds of the Old Testament, who always had their own tribe and their own herd with them. Without a doubt, these valleys still house some of the old shepherds who constitute their memory, and who prophesy in their relative solitude.

The power of a postcard The power of a postcard

Something physical and magical still remains in a postcard.

I sent a view of the Dolomites to a friend, whom I later asked, out of curiosity, what he could see. He answered me saying that he could see a world that has disappeared, that was still sending out imperceptible signals, that drew him near to the Dolomites and their secrets, because the postcard had been sent from “down there”. As though the pale mountains had transmitted something of their power to the postcard, acting in the present, from a drawer, from a shelf, perhaps in the light of a house on Garda; far from the scenery of the city.

|

|

t brown.

t brown. Is there such a thing as Dolomite obscurity? Do they produce shadows like the other mountains, of sandstone, schist and granite? During this summer I doubt it, because the pale mountains do not bring their shadowy mass onto the nature that is the prisoner of these great porous walls, made of limestone and magnesium. They remain distant, like the Moon, which is ever-present yet constantly coloured with discretion. It is far away, silky, cold. And the mountains are far away, silky and cold. Their plasticity is clear, perfect and always moving.

Is there such a thing as Dolomite obscurity? Do they produce shadows like the other mountains, of sandstone, schist and granite? During this summer I doubt it, because the pale mountains do not bring their shadowy mass onto the nature that is the prisoner of these great porous walls, made of limestone and magnesium. They remain distant, like the Moon, which is ever-present yet constantly coloured with discretion. It is far away, silky, cold. And the mountains are far away, silky and cold. Their plasticity is clear, perfect and always moving. The Bastiani fortress and the waltz

The Bastiani fortress and the waltz  The power of a postcard

The power of a postcard