| |

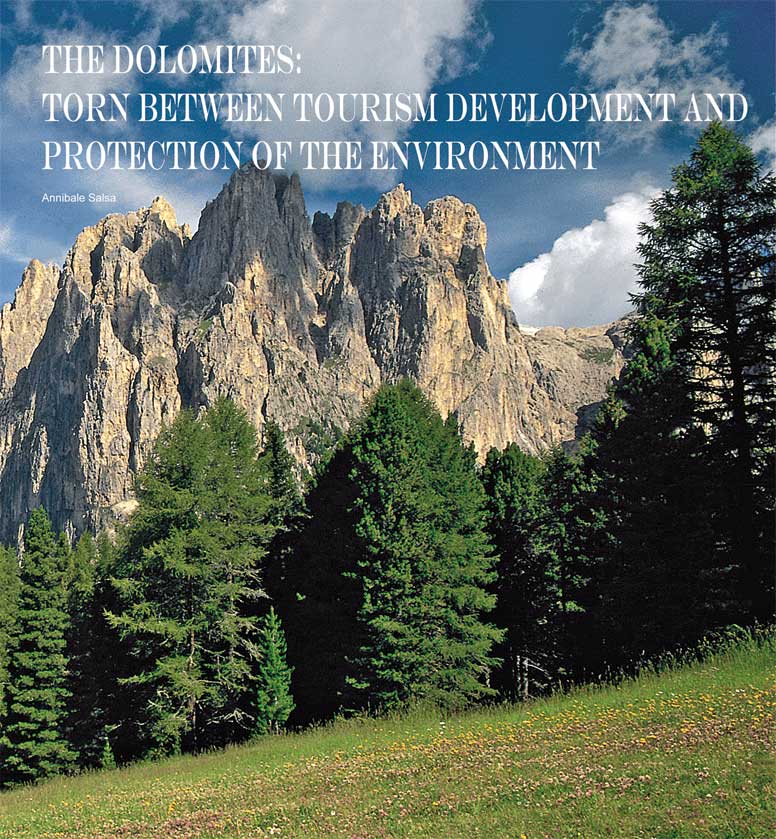

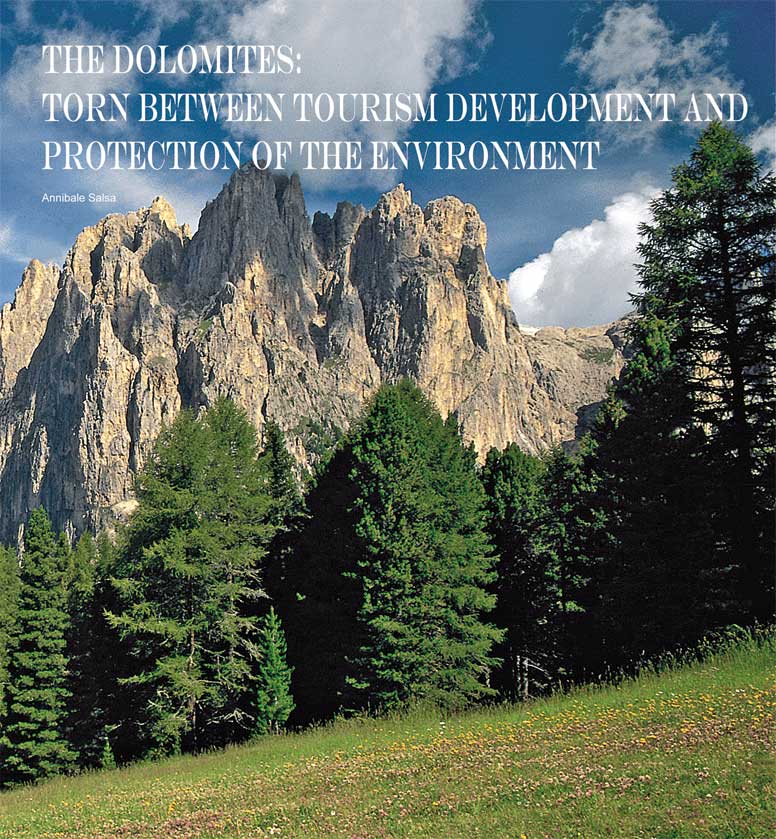

It is a widespread opinion that tourism and environmental protection represent two extremes which are difficult to reconcile. Tourist operators and residents, who have their own particular interests in an area, often see the imposition of environmental protection measures as restrictions to development. Every time that the subject of National Parks is debated, the same nightmare  almost always seems to resurface: the issue of those who have to suffer under restrictive conditions which take no account of the legitimate needs of the people living in these areas of particular environmental interest. There are differing and sometimes clashing ideas about conservation measures, which still hark back to old ideological prejudices founded on the opposing notions of the “Yes Culture”, which believes that tourism requires a constant upgrading of its infrastructure, and the “No Culture”, totally fixed on the sole idea of conservation. Given more critical analysis and freed from the fundamentalist vision, one can see that this adoption of diametrically opposed positions is both unsubstantiated and naïve at the same time. If we examine the data for tourism in the Alps, we can see can that the dynamics of visitor-flow register particularly negative trends in those areas which, in the recent past, witnessed an exponential increase in second homes. Little attention was paid to this gentle movement, the transmigration of urban and metropolitan ways of life into the valleys and villages. On the other hand, a relatively faithful client base has been maintained by those areas which have shown attention to eco-sustainability and to care of their agricultural and pastoral landscape: a type of tourism which is not so much specifically naturalistic as attentive to the balance between man and nature. An example one can quote is the Swiss UNESCO site of the Jungfrau, where little trains and cog-railways form an integral part of a man-made landscape, and tourist presence has maintained appreciably high levels. almost always seems to resurface: the issue of those who have to suffer under restrictive conditions which take no account of the legitimate needs of the people living in these areas of particular environmental interest. There are differing and sometimes clashing ideas about conservation measures, which still hark back to old ideological prejudices founded on the opposing notions of the “Yes Culture”, which believes that tourism requires a constant upgrading of its infrastructure, and the “No Culture”, totally fixed on the sole idea of conservation. Given more critical analysis and freed from the fundamentalist vision, one can see that this adoption of diametrically opposed positions is both unsubstantiated and naïve at the same time. If we examine the data for tourism in the Alps, we can see can that the dynamics of visitor-flow register particularly negative trends in those areas which, in the recent past, witnessed an exponential increase in second homes. Little attention was paid to this gentle movement, the transmigration of urban and metropolitan ways of life into the valleys and villages. On the other hand, a relatively faithful client base has been maintained by those areas which have shown attention to eco-sustainability and to care of their agricultural and pastoral landscape: a type of tourism which is not so much specifically naturalistic as attentive to the balance between man and nature. An example one can quote is the Swiss UNESCO site of the Jungfrau, where little trains and cog-railways form an integral part of a man-made landscape, and tourist presence has maintained appreciably high levels.

Now the Dolomites, after receiving their prestigious Unesco recognition, have also been called upon to take up the “challenge of complexity”, under which signs of human activity represent added value when set against our natural heritage. The landscape of the Dolomites is firmly linked to our physical and mental images of the peaks and crags, the changing colors of dawn and sunset, the strange structure of the rock formations. But we must still ask ourselves: what would the Monte Pallidi be like if human beings, over the centuries, had not built their settlements on this high ground? What sort of landscape would we have if it had not been put under cultivation, transforming the impenetrable forests of old into fields, pastures and managed woodland? When we think about the Dolomites our imagination also conjures up little villages perched on the high mountain slopes, to areas of level ground with shepherd’s huts, to sunlit clearings in the forest. However, the architecture of the hotels and refuges, the farmhouses and barns, the infrastructure of paths and connecting roads, all contribute towards the characteristic map of the Dolomites. An embalming of the landscape does no good service to the cause of ecology. There is, however, some movement amongst ecologists towards the idea that nature should be allowed to reclaim those areas torn apart by man. Re-naturalization, which has been causing interest in many abandoned mountain districts, is a policy which creates homologation of the landscape, uniformity in coloration and a fall in biodiversity. These observations certainly do not apply to every form of human intervention. A correct use of technology in fact imposes rigorous respect for the strict limits beyond which one can precipitate the “boomerang effect”, with unimaginable consequences. The complexity”, under which signs of human activity represent added value when set against our natural heritage. The landscape of the Dolomites is firmly linked to our physical and mental images of the peaks and crags, the changing colors of dawn and sunset, the strange structure of the rock formations. But we must still ask ourselves: what would the Monte Pallidi be like if human beings, over the centuries, had not built their settlements on this high ground? What sort of landscape would we have if it had not been put under cultivation, transforming the impenetrable forests of old into fields, pastures and managed woodland? When we think about the Dolomites our imagination also conjures up little villages perched on the high mountain slopes, to areas of level ground with shepherd’s huts, to sunlit clearings in the forest. However, the architecture of the hotels and refuges, the farmhouses and barns, the infrastructure of paths and connecting roads, all contribute towards the characteristic map of the Dolomites. An embalming of the landscape does no good service to the cause of ecology. There is, however, some movement amongst ecologists towards the idea that nature should be allowed to reclaim those areas torn apart by man. Re-naturalization, which has been causing interest in many abandoned mountain districts, is a policy which creates homologation of the landscape, uniformity in coloration and a fall in biodiversity. These observations certainly do not apply to every form of human intervention. A correct use of technology in fact imposes rigorous respect for the strict limits beyond which one can precipitate the “boomerang effect”, with unimaginable consequences. The  “mountain museum” should not represent the model to look to. Nature and human activity are, in fact, united in a logical and dynamic process of change and transformation. The importance of environmental protection measures should therefore be seen from the point of view of appreciating the intrinsic value of an area, of putting enlightened governance into place. Such measures should lead to a growth in the knowledge that, with good management of an area, tourism is not penalized: rather it is directed towards those good practices which can bring about excellent results. How does one escape, therefore, form the apparently intractable dichotomy between the unconditional “Yes” culture and the equally firm “No”? In just one way: a culture of “How”, which recognizes the value and sense of limitations as against the technocratic desire for the unlimited. “mountain museum” should not represent the model to look to. Nature and human activity are, in fact, united in a logical and dynamic process of change and transformation. The importance of environmental protection measures should therefore be seen from the point of view of appreciating the intrinsic value of an area, of putting enlightened governance into place. Such measures should lead to a growth in the knowledge that, with good management of an area, tourism is not penalized: rather it is directed towards those good practices which can bring about excellent results. How does one escape, therefore, form the apparently intractable dichotomy between the unconditional “Yes” culture and the equally firm “No”? In just one way: a culture of “How”, which recognizes the value and sense of limitations as against the technocratic desire for the unlimited.

The Dolomites, like all European mountains, are a place very influenced by the workings of man. The abstract principles of a “wilderness” philosophy cannot be applied to them, because then the remedy would certainly be worse than the illness. UNESCO intends to protect the naturalistic aspects of the Dolomites, without interfering in the places inhabited by man. It falls to the inhabitants of these places to adopt a self-regulatory code so that the attraction of the Dolomite region has a future which guarantees a legacy of beauty and habitability.

Annibale Salsa

General President of the CAI (Italian Alpine Club) and past chairman

of the "Population & Culture” Working Group of the Convention of the Alps.

Ex-lecturer of Anthropology in Genova University.

Opere di:

Claudio Menegazzi |

|

almost always seems to resurface: the issue of those who have to suffer under restrictive conditions which take no account of the legitimate needs of the people living in these areas of particular environmental interest. There are differing and sometimes clashing ideas about conservation measures, which still hark back to old ideological prejudices founded on the opposing notions of the “Yes Culture”, which believes that tourism requires a constant upgrading of its infrastructure, and the “No Culture”, totally fixed on the sole idea of conservation. Given more critical analysis and freed from the fundamentalist vision, one can see that this adoption of diametrically opposed positions is both unsubstantiated and naïve at the same time. If we examine the data for tourism in the Alps, we can see can that the dynamics of visitor-flow register particularly negative trends in those areas which, in the recent past, witnessed an exponential increase in second homes. Little attention was paid to this gentle movement, the transmigration of urban and metropolitan ways of life into the valleys and villages. On the other hand, a relatively faithful client base has been maintained by those areas which have shown attention to eco-sustainability and to care of their agricultural and pastoral landscape: a type of tourism which is not so much specifically naturalistic as attentive to the balance between man and nature. An example one can quote is the Swiss UNESCO site of the Jungfrau, where little trains and cog-railways form an integral part of a man-made landscape, and tourist presence has maintained appreciably high levels.

almost always seems to resurface: the issue of those who have to suffer under restrictive conditions which take no account of the legitimate needs of the people living in these areas of particular environmental interest. There are differing and sometimes clashing ideas about conservation measures, which still hark back to old ideological prejudices founded on the opposing notions of the “Yes Culture”, which believes that tourism requires a constant upgrading of its infrastructure, and the “No Culture”, totally fixed on the sole idea of conservation. Given more critical analysis and freed from the fundamentalist vision, one can see that this adoption of diametrically opposed positions is both unsubstantiated and naïve at the same time. If we examine the data for tourism in the Alps, we can see can that the dynamics of visitor-flow register particularly negative trends in those areas which, in the recent past, witnessed an exponential increase in second homes. Little attention was paid to this gentle movement, the transmigration of urban and metropolitan ways of life into the valleys and villages. On the other hand, a relatively faithful client base has been maintained by those areas which have shown attention to eco-sustainability and to care of their agricultural and pastoral landscape: a type of tourism which is not so much specifically naturalistic as attentive to the balance between man and nature. An example one can quote is the Swiss UNESCO site of the Jungfrau, where little trains and cog-railways form an integral part of a man-made landscape, and tourist presence has maintained appreciably high levels.  complexity”, under which signs of human activity represent added value when set against our natural heritage. The landscape of the Dolomites is firmly linked to our physical and mental images of the peaks and crags, the changing colors of dawn and sunset, the strange structure of the rock formations. But we must still ask ourselves: what would the Monte Pallidi be like if human beings, over the centuries, had not built their settlements on this high ground? What sort of landscape would we have if it had not been put under cultivation, transforming the impenetrable forests of old into fields, pastures and managed woodland? When we think about the Dolomites our imagination also conjures up little villages perched on the high mountain slopes, to areas of level ground with shepherd’s huts, to sunlit clearings in the forest. However, the architecture of the hotels and refuges, the farmhouses and barns, the infrastructure of paths and connecting roads, all contribute towards the characteristic map of the Dolomites. An embalming of the landscape does no good service to the cause of ecology. There is, however, some movement amongst ecologists towards the idea that nature should be allowed to reclaim those areas torn apart by man. Re-naturalization, which has been causing interest in many abandoned mountain districts, is a policy which creates homologation of the landscape, uniformity in coloration and a fall in biodiversity. These observations certainly do not apply to every form of human intervention. A correct use of technology in fact imposes rigorous respect for the strict limits beyond which one can precipitate the “boomerang effect”, with unimaginable consequences. The

complexity”, under which signs of human activity represent added value when set against our natural heritage. The landscape of the Dolomites is firmly linked to our physical and mental images of the peaks and crags, the changing colors of dawn and sunset, the strange structure of the rock formations. But we must still ask ourselves: what would the Monte Pallidi be like if human beings, over the centuries, had not built their settlements on this high ground? What sort of landscape would we have if it had not been put under cultivation, transforming the impenetrable forests of old into fields, pastures and managed woodland? When we think about the Dolomites our imagination also conjures up little villages perched on the high mountain slopes, to areas of level ground with shepherd’s huts, to sunlit clearings in the forest. However, the architecture of the hotels and refuges, the farmhouses and barns, the infrastructure of paths and connecting roads, all contribute towards the characteristic map of the Dolomites. An embalming of the landscape does no good service to the cause of ecology. There is, however, some movement amongst ecologists towards the idea that nature should be allowed to reclaim those areas torn apart by man. Re-naturalization, which has been causing interest in many abandoned mountain districts, is a policy which creates homologation of the landscape, uniformity in coloration and a fall in biodiversity. These observations certainly do not apply to every form of human intervention. A correct use of technology in fact imposes rigorous respect for the strict limits beyond which one can precipitate the “boomerang effect”, with unimaginable consequences. The  “mountain museum” should not represent the model to look to. Nature and human activity are, in fact, united in a logical and dynamic process of change and transformation. The importance of environmental protection measures should therefore be seen from the point of view of appreciating the intrinsic value of an area, of putting enlightened governance into place. Such measures should lead to a growth in the knowledge that, with good management of an area, tourism is not penalized: rather it is directed towards those good practices which can bring about excellent results. How does one escape, therefore, form the apparently intractable dichotomy between the unconditional “Yes” culture and the equally firm “No”? In just one way: a culture of “How”, which recognizes the value and sense of limitations as against the technocratic desire for the unlimited.

“mountain museum” should not represent the model to look to. Nature and human activity are, in fact, united in a logical and dynamic process of change and transformation. The importance of environmental protection measures should therefore be seen from the point of view of appreciating the intrinsic value of an area, of putting enlightened governance into place. Such measures should lead to a growth in the knowledge that, with good management of an area, tourism is not penalized: rather it is directed towards those good practices which can bring about excellent results. How does one escape, therefore, form the apparently intractable dichotomy between the unconditional “Yes” culture and the equally firm “No”? In just one way: a culture of “How”, which recognizes the value and sense of limitations as against the technocratic desire for the unlimited.