INFORMATION, CHOICES AND DEVELOPMENT

Tito Boeri

Scientific advisor to the Economics Festival

When I attended secondary school, not a day went by without finding a flyer in my hand when I got to school. Often more than one. Today, they are rare. To express a widely-shared discomfort, one no longer writes a manifesto, calls a meeting or organises a demonstration. People are turning to the unions, local associations or political parties increasingly less often. There is no longer a mechanism for transitioning from the particular to the general. We need to find a way to be featured on the front page. The Innse workers who climbed a crane to protest the closure of their factory have learned that lesson.

Their voice was heard. But what about the others? The attention of the media is very selective. Nowadays, even workers who climb up on the roof don't make the news. You need to occupy the former Asinara prison, like the Vinyls workers who are receiving redundancy payments. What will they think of next after the “Isola dei Cassintegrati” (Island of Redundant Workers, the ironic name of the Asinara protest)? The world we live in has more and more information and less and less attention. The most limited resource is the grey matter between our ears. The new “padroni del vapore” (owners of the steam, the title of a book by Ernesto Rossi) are the owners of attention, those who control the media, the most watched programmes. Today, they count more than those who hold the physical capital, they have much more influence than the owners of factories, railroads and even large shopping centres. Their voice was heard. But what about the others? The attention of the media is very selective. Nowadays, even workers who climb up on the roof don't make the news. You need to occupy the former Asinara prison, like the Vinyls workers who are receiving redundancy payments. What will they think of next after the “Isola dei Cassintegrati” (Island of Redundant Workers, the ironic name of the Asinara protest)? The world we live in has more and more information and less and less attention. The most limited resource is the grey matter between our ears. The new “padroni del vapore” (owners of the steam, the title of a book by Ernesto Rossi) are the owners of attention, those who control the media, the most watched programmes. Today, they count more than those who hold the physical capital, they have much more influence than the owners of factories, railroads and even large shopping centres.

A lot of information is costly to produce but not to publish and reproduce. There are high fixed costs for gathering information and very low marginal costs for broadcasting it. Technological innovations like the Internet have made information potentially available to billions of people at zero cost. Just like it is increasingly easy to spread information, it is also increasingly easy to expropriate it without acknowledging the source, the intellectual property. This can make it impossible to sell information and, thus, to recover the costs of production by those who incurred them. It can also lead to the collapse, or the drastic resizing, of entire information markets, such as that of printed paper, which have high production costs. A lot of information is costly to produce but not to publish and reproduce. There are high fixed costs for gathering information and very low marginal costs for broadcasting it. Technological innovations like the Internet have made information potentially available to billions of people at zero cost. Just like it is increasingly easy to spread information, it is also increasingly easy to expropriate it without acknowledging the source, the intellectual property. This can make it impossible to sell information and, thus, to recover the costs of production by those who incurred them. It can also lead to the collapse, or the drastic resizing, of entire information markets, such as that of printed paper, which have high production costs.

The crisis of the information producers can make them especially vulnerable to the influence of economic and political power. One increasingly important source of financing for information producers who are not able to get paid by the users is advertising. But even advertising can be used for blackmail. It will not be difficult to find fitting examples. This pressure and influence are often opaque, not very transparent and, because of this, those who access information are not able to assess its nature and find it difficult to tell if, and to what extent, it is biased. This raises worrisome questions about the democratic control of a country by its citizens. There are also significant economic costs in disinformation. Without information, prices cease to perform their function and markets cannot operate. One immediate example of the costs of the lack of information, or the presence of not very credible information, are the causes of the Great Recession of 2008-9. The crisis of the information producers can make them especially vulnerable to the influence of economic and political power. One increasingly important source of financing for information producers who are not able to get paid by the users is advertising. But even advertising can be used for blackmail. It will not be difficult to find fitting examples. This pressure and influence are often opaque, not very transparent and, because of this, those who access information are not able to assess its nature and find it difficult to tell if, and to what extent, it is biased. This raises worrisome questions about the democratic control of a country by its citizens. There are also significant economic costs in disinformation. Without information, prices cease to perform their function and markets cannot operate. One immediate example of the costs of the lack of information, or the presence of not very credible information, are the causes of the Great Recession of 2008-9.  The collapse of entire segments of the financial markets was produced precisely by increasingly marked information imbalances: banks no longer trusted each other because they knew that there were all those “toxic securities” in circulation and the banks that held large quantities of them would have done everything not to reveal it. Even when banks held really very few “toxic securities” and were, thus, anxious to publicise the health of their balance sheets, they had no way to make the reassuring information they wanted to give the markets look credible. The collapse of entire segments of the financial markets was produced precisely by increasingly marked information imbalances: banks no longer trusted each other because they knew that there were all those “toxic securities” in circulation and the banks that held large quantities of them would have done everything not to reveal it. Even when banks held really very few “toxic securities” and were, thus, anxious to publicise the health of their balance sheets, they had no way to make the reassuring information they wanted to give the markets look credible.  In fact, information has value to the extent that it is credible. If someone is looking for work and wants to convince a potential employer about his qualifications, it's just not enough to say that he would be able to do a good job. He needs to find a way to make his qualifications visible to a potential employer in order to convince him that he is making the right choice. If he has diplomas and degrees to show, he provides them even if only to indicate his abilities. Someone who was good enough to earn a degree will perform other tasks equally well. In fact, information has value to the extent that it is credible. If someone is looking for work and wants to convince a potential employer about his qualifications, it's just not enough to say that he would be able to do a good job. He needs to find a way to make his qualifications visible to a potential employer in order to convince him that he is making the right choice. If he has diplomas and degrees to show, he provides them even if only to indicate his abilities. Someone who was good enough to earn a degree will perform other tasks equally well.

But employers don't always want to be reassured about the quality of their employees. I will tell you the chilling and depressing story of something that I witnessed several days ago. A young researcher was hired by a public agency. The work was often routine and well below his expectations and his relationship with his supervisor was formal. But, every so often, there was an opportunity to talk and, during one of these, the supervisor offered the following lesson from his life experience: “You're kidding yourself if you think that your brilliant degrees from foreign universities will help your career. Look, to get my appointment I had to put together a thick file of embarrassing facts that would make me blackmailable. This file assures the person who appointed me that I will be obedient, it's the ticket for my career.”

Criminal organisations are based precisely on exchanges of this type, in which hierarchical superiors ensure the loyalty of their underlings through blackmail made possible by the possession of compromising information about them. It must remain confidential so that it can be used against them. Perhaps the real reason why important members of Italy's ruling class don't tolerate wiretaps is because they make compromising information public that needs to remain confidential into order the cement hierarchical relationships or balances of power supported by reciprocal blackmail. Criminal organisations are based precisely on exchanges of this type, in which hierarchical superiors ensure the loyalty of their underlings through blackmail made possible by the possession of compromising information about them. It must remain confidential so that it can be used against them. Perhaps the real reason why important members of Italy's ruling class don't tolerate wiretaps is because they make compromising information public that needs to remain confidential into order the cement hierarchical relationships or balances of power supported by reciprocal blackmail.

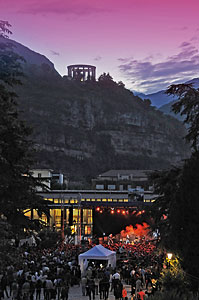

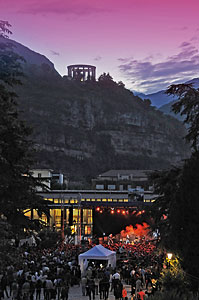

We will talk of these and other subjects at the fifth edition of the Festival. We will attempt to provide you with tools for selecting economic information based on their importance and reliability and for reading the statistics so often scoffed at by politicians. Once again this year, we will try to deserve your attention.

|

NUMBER 9

NUMBER 9

Their voice was heard. But what about the others? The attention of the media is very selective. Nowadays, even workers who climb up on the roof don't make the news. You need to occupy the former Asinara prison, like the Vinyls workers who are receiving redundancy payments. What will they think of next after the “Isola dei Cassintegrati” (Island of Redundant Workers, the ironic name of the Asinara protest)? The world we live in has more and more information and less and less attention. The most limited resource is the grey matter between our ears. The new “padroni del vapore” (owners of the steam, the title of a book by Ernesto Rossi) are the owners of attention, those who control the media, the most watched programmes. Today, they count more than those who hold the physical capital, they have much more influence than the owners of factories, railroads and even large shopping centres.

Their voice was heard. But what about the others? The attention of the media is very selective. Nowadays, even workers who climb up on the roof don't make the news. You need to occupy the former Asinara prison, like the Vinyls workers who are receiving redundancy payments. What will they think of next after the “Isola dei Cassintegrati” (Island of Redundant Workers, the ironic name of the Asinara protest)? The world we live in has more and more information and less and less attention. The most limited resource is the grey matter between our ears. The new “padroni del vapore” (owners of the steam, the title of a book by Ernesto Rossi) are the owners of attention, those who control the media, the most watched programmes. Today, they count more than those who hold the physical capital, they have much more influence than the owners of factories, railroads and even large shopping centres. A lot of information is costly to produce but not to publish and reproduce. There are high fixed costs for gathering information and very low marginal costs for broadcasting it. Technological innovations like the Internet have made information potentially available to billions of people at zero cost. Just like it is increasingly easy to spread information, it is also increasingly easy to expropriate it without acknowledging the source, the intellectual property. This can make it impossible to sell information and, thus, to recover the costs of production by those who incurred them. It can also lead to the collapse, or the drastic resizing, of entire information markets, such as that of printed paper, which have high production costs.

A lot of information is costly to produce but not to publish and reproduce. There are high fixed costs for gathering information and very low marginal costs for broadcasting it. Technological innovations like the Internet have made information potentially available to billions of people at zero cost. Just like it is increasingly easy to spread information, it is also increasingly easy to expropriate it without acknowledging the source, the intellectual property. This can make it impossible to sell information and, thus, to recover the costs of production by those who incurred them. It can also lead to the collapse, or the drastic resizing, of entire information markets, such as that of printed paper, which have high production costs. The crisis of the information producers can make them especially vulnerable to the influence of economic and political power. One increasingly important source of financing for information producers who are not able to get paid by the users is advertising. But even advertising can be used for blackmail. It will not be difficult to find fitting examples. This pressure and influence are often opaque, not very transparent and, because of this, those who access information are not able to assess its nature and find it difficult to tell if, and to what extent, it is biased. This raises worrisome questions about the democratic control of a country by its citizens. There are also significant economic costs in disinformation. Without information, prices cease to perform their function and markets cannot operate. One immediate example of the costs of the lack of information, or the presence of not very credible information, are the causes of the Great Recession of 2008-9.

The crisis of the information producers can make them especially vulnerable to the influence of economic and political power. One increasingly important source of financing for information producers who are not able to get paid by the users is advertising. But even advertising can be used for blackmail. It will not be difficult to find fitting examples. This pressure and influence are often opaque, not very transparent and, because of this, those who access information are not able to assess its nature and find it difficult to tell if, and to what extent, it is biased. This raises worrisome questions about the democratic control of a country by its citizens. There are also significant economic costs in disinformation. Without information, prices cease to perform their function and markets cannot operate. One immediate example of the costs of the lack of information, or the presence of not very credible information, are the causes of the Great Recession of 2008-9.  The collapse of entire segments of the financial markets was produced precisely by increasingly marked information imbalances: banks no longer trusted each other because they knew that there were all those “toxic securities” in circulation and the banks that held large quantities of them would have done everything not to reveal it. Even when banks held really very few “toxic securities” and were, thus, anxious to publicise the health of their balance sheets, they had no way to make the reassuring information they wanted to give the markets look credible.

The collapse of entire segments of the financial markets was produced precisely by increasingly marked information imbalances: banks no longer trusted each other because they knew that there were all those “toxic securities” in circulation and the banks that held large quantities of them would have done everything not to reveal it. Even when banks held really very few “toxic securities” and were, thus, anxious to publicise the health of their balance sheets, they had no way to make the reassuring information they wanted to give the markets look credible.  In fact, information has value to the extent that it is credible. If someone is looking for work and wants to convince a potential employer about his qualifications, it's just not enough to say that he would be able to do a good job. He needs to find a way to make his qualifications visible to a potential employer in order to convince him that he is making the right choice. If he has diplomas and degrees to show, he provides them even if only to indicate his abilities. Someone who was good enough to earn a degree will perform other tasks equally well.

In fact, information has value to the extent that it is credible. If someone is looking for work and wants to convince a potential employer about his qualifications, it's just not enough to say that he would be able to do a good job. He needs to find a way to make his qualifications visible to a potential employer in order to convince him that he is making the right choice. If he has diplomas and degrees to show, he provides them even if only to indicate his abilities. Someone who was good enough to earn a degree will perform other tasks equally well. Criminal organisations are based precisely on exchanges of this type, in which hierarchical superiors ensure the loyalty of their underlings through blackmail made possible by the possession of compromising information about them. It must remain confidential so that it can be used against them. Perhaps the real reason why important members of Italy's ruling class don't tolerate wiretaps is because they make compromising information public that needs to remain confidential into order the cement hierarchical relationships or balances of power supported by reciprocal blackmail.

Criminal organisations are based precisely on exchanges of this type, in which hierarchical superiors ensure the loyalty of their underlings through blackmail made possible by the possession of compromising information about them. It must remain confidential so that it can be used against them. Perhaps the real reason why important members of Italy's ruling class don't tolerate wiretaps is because they make compromising information public that needs to remain confidential into order the cement hierarchical relationships or balances of power supported by reciprocal blackmail.