Interview with Jaques Wagner of Bahia, Brazil

Mariapia Ciaghi and Guillermo Ortega Noriega

In the interwoven fabric of human existence, there are those whose sole mission is to devote themselves exclusively to their work. They work and work, for twenty-four hours a day. This, they think, is what the men and women of this world were born to do - with some exceptions, of course. This paper, inspired by its usual sense of mission, and resolved to investigate a situation that Europeans in particular continue to focus on because of certain historical - and also commercial - links, has determined to go back to the beginning, or rather to examine a milestone in this immense country: Bahía, in Brazil. Thus, it has been decided to present in these pages a profile of a worker who occupies a position of enormous political importance, and is empowered with charting the new course of the State of Bahía.

Guillermo Ortega Noriega: You were born in Río de Janeiro in March 1951, and practically launched your political career at your bar-mitzvah, when you spoke on behalf of all young Jews. With the success you achieved, you clearly discovered your vocation. How did you come to arrive in Bahía?

Jaques Wagner: I studied engineering at the Catholic University of Río de Janeiro, and have been involved in politics ever since my adolescence, when I joined the Zionist movement. At the University, I was President of the Academic Council at a time of unrest for the student movement, which was an important focus of resistance to the dictatorship.  The repression persecuted the administration, and this too impeded my studies. We suffered other restrictions as well. In1972 I arrived in the State of Bahía, already married and with my first child, Mariana. As I couldn’t give up my studies - I wasn’t qualified as an engineer and I didn’t have any other profession – I lived in a house which I myself constructed in Itacaranha, a district on the edge of the Salvador railway line, working as an assistant. Then, quite by chance, I heard about a course in industrial hydraulics being promoted by the priests of the local parish. So I attended that, and got my first job in a factory in a petrochemical complex Camaçari, at a time of enormous construction work. I had never stopped being politically active, even illegally, and got involved in the management of the petrochemical workers union, becoming the president. Some years later, at a congress in Salvador, I met the union leader who struck terror into the dictators: Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. Together we founded the PT (Partido de los Trabajadores): Lula da Silva was the first national president of the party and I was the first president of the Bahía section. All my life has been built around Bahía. Bahía is the homeland of Brazil, a warm and generous mother who welcomed many Bahians who, like me, happened to have been born elsewhere. For me, being a Bahian was a choice, and the greatest matter of pride in my life was being elected to govern this State. The repression persecuted the administration, and this too impeded my studies. We suffered other restrictions as well. In1972 I arrived in the State of Bahía, already married and with my first child, Mariana. As I couldn’t give up my studies - I wasn’t qualified as an engineer and I didn’t have any other profession – I lived in a house which I myself constructed in Itacaranha, a district on the edge of the Salvador railway line, working as an assistant. Then, quite by chance, I heard about a course in industrial hydraulics being promoted by the priests of the local parish. So I attended that, and got my first job in a factory in a petrochemical complex Camaçari, at a time of enormous construction work. I had never stopped being politically active, even illegally, and got involved in the management of the petrochemical workers union, becoming the president. Some years later, at a congress in Salvador, I met the union leader who struck terror into the dictators: Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. Together we founded the PT (Partido de los Trabajadores): Lula da Silva was the first national president of the party and I was the first president of the Bahía section. All my life has been built around Bahía. Bahía is the homeland of Brazil, a warm and generous mother who welcomed many Bahians who, like me, happened to have been born elsewhere. For me, being a Bahian was a choice, and the greatest matter of pride in my life was being elected to govern this State.

Mariapia Ciaghi: Brazil is an important country for Italy because 24 million sons and grandsons of Italians and Italian citizens live here; including Marisa, wife of Lula, the Minister for Development, Industry and Commerce, Luiz Fernando Furlan, the Governor of the State of San Paolo, José Serra and many other personalities from the worlds of politics, business and culture. What could its role be with relation to the October 2010 elections in Italy?

JW: Italy forms part of Brazil’s multinational soul. I believe that, as a friendly country, the best role that Italy can play is that of supporting Brazil in its progress to realizing the full maturity of its democratic institutions. This will allow Brazil to be a better country for all its citizens, including the descendants of Italians, and provide more opportunities in our country. We must realize that both parties concerned have benefitted from the contributions made by previous generations. This is equally true for agriculture, industry and also for politics. For it was the anarchist trade-unionists, the combative founders of the Brazilian workers’ movement, who planted the seeds of rebellion. However, we are only a year away from the World Cup, and it looks pretty certain that Brazil could be meeting Italy in the final... JW: Italy forms part of Brazil’s multinational soul. I believe that, as a friendly country, the best role that Italy can play is that of supporting Brazil in its progress to realizing the full maturity of its democratic institutions. This will allow Brazil to be a better country for all its citizens, including the descendants of Italians, and provide more opportunities in our country. We must realize that both parties concerned have benefitted from the contributions made by previous generations. This is equally true for agriculture, industry and also for politics. For it was the anarchist trade-unionists, the combative founders of the Brazilian workers’ movement, who planted the seeds of rebellion. However, we are only a year away from the World Cup, and it looks pretty certain that Brazil could be meeting Italy in the final...

GON: In his book “El poblamiento de Salvador” (The Peopling of Salvador), ex-Professor Thales de Azevedo claims that Bahía in Brazil is an example of a multi-racial society where discrimination can be seen mainly in the abuse of economic power. He maintains that the increasing social violence of today could be the result of such a behavioral characteristic already embedded in the collective psyche, or indeed of a huge and uncontrolled use of forms of electronic communication.

JW: To start with, I really think I should state that fortunately we are reversing the upward curve in the statistical data as regards violence. A good example of this is our Carnival: for the third consecutive year the incidence figures in the police records have been significantly reduced; and this is at a time when about 1.8 million people are concentrated into a relatively small area in order to drink and dance. In ordinary life, we have also obtained some important results, with large investments in expanding and training our police forces and in improving the infrastructure. As to the causes of violence, I think it’s an extremely complex social phenomenom with a single explanation. The central issue, of course, is the long-term problem of social exclusion, which has deprived millions of citizens of access to the fundamental rights of every human being, such as education, health, work, food and a home. Brazil has made great strides with regard to inequality, especially under the premiership of Lula. Nevertheless, there is no way that five centuries can be corrected in eight years. The fact is that the Brazilian people are aware of the issue, and so are exercising their sacred right to vote with a conscience that is growing in strength. People are getting more demanding and more independent of the messages addressed to them by the communication media which, certainly, have never been so free before in the entire history of this country called Brazil. JW: To start with, I really think I should state that fortunately we are reversing the upward curve in the statistical data as regards violence. A good example of this is our Carnival: for the third consecutive year the incidence figures in the police records have been significantly reduced; and this is at a time when about 1.8 million people are concentrated into a relatively small area in order to drink and dance. In ordinary life, we have also obtained some important results, with large investments in expanding and training our police forces and in improving the infrastructure. As to the causes of violence, I think it’s an extremely complex social phenomenom with a single explanation. The central issue, of course, is the long-term problem of social exclusion, which has deprived millions of citizens of access to the fundamental rights of every human being, such as education, health, work, food and a home. Brazil has made great strides with regard to inequality, especially under the premiership of Lula. Nevertheless, there is no way that five centuries can be corrected in eight years. The fact is that the Brazilian people are aware of the issue, and so are exercising their sacred right to vote with a conscience that is growing in strength. People are getting more demanding and more independent of the messages addressed to them by the communication media which, certainly, have never been so free before in the entire history of this country called Brazil.

MC: On various occasions you have shown the willingness of the State of Bahia to collaborate with the Italian government in the tourism sector, in motor manufacturing, in small-scale farming, and in promotion of local products. Do you think the conditions exist to pursue this line of cooperation? MC: On various occasions you have shown the willingness of the State of Bahia to collaborate with the Italian government in the tourism sector, in motor manufacturing, in small-scale farming, and in promotion of local products. Do you think the conditions exist to pursue this line of cooperation?

JW: Yes, I am increasingly convinced that we have plenty of opportunities available. I would like to use this occasion to invite Italian investors who want to invest in a place where the regulations are totally clear and transparent, where agreements are respected and where the people are happy but hard-working. I have heard from the international heads of Ford and other big companies established in Bahía that our workforce achieves the greatest average output of all the countries they are involved in. We have an excellent program to attract investments, with fiscal incentives, good infrastructure, honest and dedicated workers and a country with huge unexploited potential. We are witnessing an explosion in important sectors of the economy such as mining, the chemical and petrochemical industries and shipbuilding, not to mention tourism and other activities which benefit from the notable creative talents of the Bahians. I do not welcome with open arms those who are simply venture capitalists, but out lay out the red carpet for anyone who really wants to contribute to the development of Bahía. Anyone who puts his faith in us will certainly not be let down.

GON: Do you believe that, in general, Europe and South America can collaborate in the various global scenarios, whether in confronting major crises, or in strengthening a system of multinational relationships in the field of commerce and in the defense of peace.

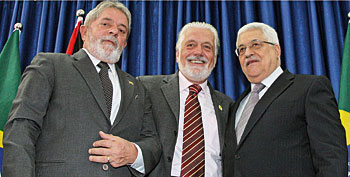

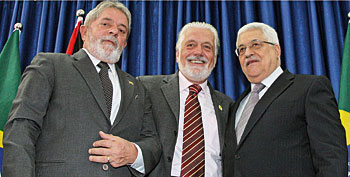

JW: Yes, an example of this is the recent Brazilian mission to the Middle East led by President Lula, in which I myself participated as his guest. Brazilian diplomacy was involved in the revival of the Oslo Accord, because we are convinced of the necessity – not just the possibility – of co-existence between Israel and the Palestinian State, and we have offered to be mediators. Our proposal received a positive welcome because of our position of complete neutrality in the conflict. Brazil boasts a pacifist tradition which goes back more than a century and which frees us from all types of conflict with other countries. We have made progress in regional integration, providing a positive example with regards to the possibility of achieving economic and political growth, without such development becoming a burden for other people and nations. We have lived through some times of tension with Bolivia, in relation to contracts for the exploitation and sale of natural gas; and with Paraguay, because of the excess energy supply generated by the Itaipú dam – a bi-national enterprise – which we acquired from our Paraguayan partners. There were some who provoked a hard reaction from our president. In any case, both these questions were resolved by round-table negotiations, respecting the interests and rights of our Bolivian and Paraguayan partners without neglecting the interests of Brazil. No better method than the negotiating table has yet been invented, and I think that both the Europeans – who were so deeply affected by the horrors of the two world wars – and the South Americans are fully aware of this. JW: Yes, an example of this is the recent Brazilian mission to the Middle East led by President Lula, in which I myself participated as his guest. Brazilian diplomacy was involved in the revival of the Oslo Accord, because we are convinced of the necessity – not just the possibility – of co-existence between Israel and the Palestinian State, and we have offered to be mediators. Our proposal received a positive welcome because of our position of complete neutrality in the conflict. Brazil boasts a pacifist tradition which goes back more than a century and which frees us from all types of conflict with other countries. We have made progress in regional integration, providing a positive example with regards to the possibility of achieving economic and political growth, without such development becoming a burden for other people and nations. We have lived through some times of tension with Bolivia, in relation to contracts for the exploitation and sale of natural gas; and with Paraguay, because of the excess energy supply generated by the Itaipú dam – a bi-national enterprise – which we acquired from our Paraguayan partners. There were some who provoked a hard reaction from our president. In any case, both these questions were resolved by round-table negotiations, respecting the interests and rights of our Bolivian and Paraguayan partners without neglecting the interests of Brazil. No better method than the negotiating table has yet been invented, and I think that both the Europeans – who were so deeply affected by the horrors of the two world wars – and the South Americans are fully aware of this.

MC: Sustainable development is an objective which is now being pursued, and Brazil has the best possible conditions for modulation under its belt, the development model in this case. What changes do you think are necessary to rebuild the nation in this way? MC: Sustainable development is an objective which is now being pursued, and Brazil has the best possible conditions for modulation under its belt, the development model in this case. What changes do you think are necessary to rebuild the nation in this way?

JW: I don’t think that any country could supply a definite answer to your question. Brazil has a great opportunity to find answers and to share possible let-outs: but these would be Brazilian responses for Brazil. Our recipe is based on social dialogue, combined with a modern system of legislation and reinforced security. It’s not easy. But it’s absolutely essential to achieve a balance. I believe that this is the key word: balance. I don’t agree either with those fundamentalists who contemplate the situation and say that nothing can be done, or with those fundamentalists who believe in development at any cost. If society can make the most of all those situations and institutions which operate freely under the attentive eye of the press, then reaching a balance becomes possible.

GON: You were elected Governor of the State of Bahía in the first round of elections in October 2006. This was thanks to your amazing capacity for work and the enormous popularity you enjoy. The proposal was then confirmed that you should have direct responsibility for administering state funds for social action programs, acting in unison with President Lula, with whom you share an unconditional friendship. Do you think the Brazilian President is concealing a surprise with regard to your political future? In short, could you become a candidate for the Presidency of the Republic?

JW: Perhaps as a result of our victory here at home in 2006, when we defeated a seemingly invincible oligarchy, my name was on a list of possible candidates. But I think that was because of the electoral victory, and because I was the Governor of the largest state led by our party. I know that I have an important mission here in Bahía. Our success depends in large measure on the success of the national plan instituted with the arrival of Lula as President and, God willing, it will be strengthened when the first woman assumes our highest national office. I feel I am a man created to have arrived in Bahía as a worker and then to have become its governor. And I will strive to contribute to the election of Dilma Rousseff as president of Brazil. JW: Perhaps as a result of our victory here at home in 2006, when we defeated a seemingly invincible oligarchy, my name was on a list of possible candidates. But I think that was because of the electoral victory, and because I was the Governor of the largest state led by our party. I know that I have an important mission here in Bahía. Our success depends in large measure on the success of the national plan instituted with the arrival of Lula as President and, God willing, it will be strengthened when the first woman assumes our highest national office. I feel I am a man created to have arrived in Bahía as a worker and then to have become its governor. And I will strive to contribute to the election of Dilma Rousseff as president of Brazil.

The original text in Portuguese was revised by the Brazilian journalist Ernesto Dantas Araujo Marques.

|

NUMBER 9

NUMBER 9

The repression persecuted the administration, and this too impeded my studies. We suffered other restrictions as well. In1972 I arrived in the State of Bahía, already married and with my first child, Mariana. As I couldn’t give up my studies - I wasn’t qualified as an engineer and I didn’t have any other profession – I lived in a house which I myself constructed in Itacaranha, a district on the edge of the Salvador railway line, working as an assistant. Then, quite by chance, I heard about a course in industrial hydraulics being promoted by the priests of the local parish. So I attended that, and got my first job in a factory in a petrochemical complex Camaçari, at a time of enormous construction work. I had never stopped being politically active, even illegally, and got involved in the management of the petrochemical workers union, becoming the president. Some years later, at a congress in Salvador, I met the union leader who struck terror into the dictators: Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. Together we founded the PT (Partido de los Trabajadores): Lula da Silva was the first national president of the party and I was the first president of the Bahía section. All my life has been built around Bahía. Bahía is the homeland of Brazil, a warm and generous mother who welcomed many Bahians who, like me, happened to have been born elsewhere. For me, being a Bahian was a choice, and the greatest matter of pride in my life was being elected to govern this State.

The repression persecuted the administration, and this too impeded my studies. We suffered other restrictions as well. In1972 I arrived in the State of Bahía, already married and with my first child, Mariana. As I couldn’t give up my studies - I wasn’t qualified as an engineer and I didn’t have any other profession – I lived in a house which I myself constructed in Itacaranha, a district on the edge of the Salvador railway line, working as an assistant. Then, quite by chance, I heard about a course in industrial hydraulics being promoted by the priests of the local parish. So I attended that, and got my first job in a factory in a petrochemical complex Camaçari, at a time of enormous construction work. I had never stopped being politically active, even illegally, and got involved in the management of the petrochemical workers union, becoming the president. Some years later, at a congress in Salvador, I met the union leader who struck terror into the dictators: Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. Together we founded the PT (Partido de los Trabajadores): Lula da Silva was the first national president of the party and I was the first president of the Bahía section. All my life has been built around Bahía. Bahía is the homeland of Brazil, a warm and generous mother who welcomed many Bahians who, like me, happened to have been born elsewhere. For me, being a Bahian was a choice, and the greatest matter of pride in my life was being elected to govern this State.  JW: Italy forms part of Brazil’s multinational soul. I believe that, as a friendly country, the best role that Italy can play is that of supporting Brazil in its progress to realizing the full maturity of its democratic institutions. This will allow Brazil to be a better country for all its citizens, including the descendants of Italians, and provide more opportunities in our country. We must realize that both parties concerned have benefitted from the contributions made by previous generations. This is equally true for agriculture, industry and also for politics. For it was the anarchist trade-unionists, the combative founders of the Brazilian workers’ movement, who planted the seeds of rebellion. However, we are only a year away from the World Cup, and it looks pretty certain that Brazil could be meeting Italy in the final...

JW: Italy forms part of Brazil’s multinational soul. I believe that, as a friendly country, the best role that Italy can play is that of supporting Brazil in its progress to realizing the full maturity of its democratic institutions. This will allow Brazil to be a better country for all its citizens, including the descendants of Italians, and provide more opportunities in our country. We must realize that both parties concerned have benefitted from the contributions made by previous generations. This is equally true for agriculture, industry and also for politics. For it was the anarchist trade-unionists, the combative founders of the Brazilian workers’ movement, who planted the seeds of rebellion. However, we are only a year away from the World Cup, and it looks pretty certain that Brazil could be meeting Italy in the final...  JW: To start with, I really think I should state that fortunately we are reversing the upward curve in the statistical data as regards violence. A good example of this is our Carnival: for the third consecutive year the incidence figures in the police records have been significantly reduced; and this is at a time when about 1.8 million people are concentrated into a relatively small area in order to drink and dance. In ordinary life, we have also obtained some important results, with large investments in expanding and training our police forces and in improving the infrastructure. As to the causes of violence, I think it’s an extremely complex social phenomenom with a single explanation. The central issue, of course, is the long-term problem of social exclusion, which has deprived millions of citizens of access to the fundamental rights of every human being, such as education, health, work, food and a home. Brazil has made great strides with regard to inequality, especially under the premiership of Lula. Nevertheless, there is no way that five centuries can be corrected in eight years. The fact is that the Brazilian people are aware of the issue, and so are exercising their sacred right to vote with a conscience that is growing in strength. People are getting more demanding and more independent of the messages addressed to them by the communication media which, certainly, have never been so free before in the entire history of this country called Brazil.

JW: To start with, I really think I should state that fortunately we are reversing the upward curve in the statistical data as regards violence. A good example of this is our Carnival: for the third consecutive year the incidence figures in the police records have been significantly reduced; and this is at a time when about 1.8 million people are concentrated into a relatively small area in order to drink and dance. In ordinary life, we have also obtained some important results, with large investments in expanding and training our police forces and in improving the infrastructure. As to the causes of violence, I think it’s an extremely complex social phenomenom with a single explanation. The central issue, of course, is the long-term problem of social exclusion, which has deprived millions of citizens of access to the fundamental rights of every human being, such as education, health, work, food and a home. Brazil has made great strides with regard to inequality, especially under the premiership of Lula. Nevertheless, there is no way that five centuries can be corrected in eight years. The fact is that the Brazilian people are aware of the issue, and so are exercising their sacred right to vote with a conscience that is growing in strength. People are getting more demanding and more independent of the messages addressed to them by the communication media which, certainly, have never been so free before in the entire history of this country called Brazil.  MC: On various occasions you have shown the willingness of the State of Bahia to collaborate with the Italian government in the tourism sector, in motor manufacturing, in small-scale farming, and in promotion of local products. Do you think the conditions exist to pursue this line of cooperation?

MC: On various occasions you have shown the willingness of the State of Bahia to collaborate with the Italian government in the tourism sector, in motor manufacturing, in small-scale farming, and in promotion of local products. Do you think the conditions exist to pursue this line of cooperation? JW: Yes, an example of this is the recent Brazilian mission to the Middle East led by President Lula, in which I myself participated as his guest. Brazilian diplomacy was involved in the revival of the Oslo Accord, because we are convinced of the necessity – not just the possibility – of co-existence between Israel and the Palestinian State, and we have offered to be mediators. Our proposal received a positive welcome because of our position of complete neutrality in the conflict. Brazil boasts a pacifist tradition which goes back more than a century and which frees us from all types of conflict with other countries. We have made progress in regional integration, providing a positive example with regards to the possibility of achieving economic and political growth, without such development becoming a burden for other people and nations. We have lived through some times of tension with Bolivia, in relation to contracts for the exploitation and sale of natural gas; and with Paraguay, because of the excess energy supply generated by the Itaipú dam – a bi-national enterprise – which we acquired from our Paraguayan partners. There were some who provoked a hard reaction from our president. In any case, both these questions were resolved by round-table negotiations, respecting the interests and rights of our Bolivian and Paraguayan partners without neglecting the interests of Brazil. No better method than the negotiating table has yet been invented, and I think that both the Europeans – who were so deeply affected by the horrors of the two world wars – and the South Americans are fully aware of this.

JW: Yes, an example of this is the recent Brazilian mission to the Middle East led by President Lula, in which I myself participated as his guest. Brazilian diplomacy was involved in the revival of the Oslo Accord, because we are convinced of the necessity – not just the possibility – of co-existence between Israel and the Palestinian State, and we have offered to be mediators. Our proposal received a positive welcome because of our position of complete neutrality in the conflict. Brazil boasts a pacifist tradition which goes back more than a century and which frees us from all types of conflict with other countries. We have made progress in regional integration, providing a positive example with regards to the possibility of achieving economic and political growth, without such development becoming a burden for other people and nations. We have lived through some times of tension with Bolivia, in relation to contracts for the exploitation and sale of natural gas; and with Paraguay, because of the excess energy supply generated by the Itaipú dam – a bi-national enterprise – which we acquired from our Paraguayan partners. There were some who provoked a hard reaction from our president. In any case, both these questions were resolved by round-table negotiations, respecting the interests and rights of our Bolivian and Paraguayan partners without neglecting the interests of Brazil. No better method than the negotiating table has yet been invented, and I think that both the Europeans – who were so deeply affected by the horrors of the two world wars – and the South Americans are fully aware of this.  MC: Sustainable development is an objective which is now being pursued, and Brazil has the best possible conditions for modulation under its belt, the development model in this case. What changes do you think are necessary to rebuild the nation in this way?

MC: Sustainable development is an objective which is now being pursued, and Brazil has the best possible conditions for modulation under its belt, the development model in this case. What changes do you think are necessary to rebuild the nation in this way?  JW: Perhaps as a result of our victory here at home in 2006, when we defeated a seemingly invincible oligarchy, my name was on a list of possible candidates. But I think that was because of the electoral victory, and because I was the Governor of the largest state led by our party. I know that I have an important mission here in Bahía. Our success depends in large measure on the success of the national plan instituted with the arrival of Lula as President and, God willing, it will be strengthened when the first woman assumes our highest national office. I feel I am a man created to have arrived in Bahía as a worker and then to have become its governor. And I will strive to contribute to the election of Dilma Rousseff as president of Brazil.

JW: Perhaps as a result of our victory here at home in 2006, when we defeated a seemingly invincible oligarchy, my name was on a list of possible candidates. But I think that was because of the electoral victory, and because I was the Governor of the largest state led by our party. I know that I have an important mission here in Bahía. Our success depends in large measure on the success of the national plan instituted with the arrival of Lula as President and, God willing, it will be strengthened when the first woman assumes our highest national office. I feel I am a man created to have arrived in Bahía as a worker and then to have become its governor. And I will strive to contribute to the election of Dilma Rousseff as president of Brazil.